He was the poet, and she was the muse.

When Marianne Ihlen first me Leonard Cohen, she was crying in a small market on the Greek island of Hydra. A recently separated single mother, Marianne was a long way from her family in Norway, and having been abandoned by her philandering husband, she was overcome by the grief and sadness which came from loneliness. Weeping silently over her basket containing bottled water and milk, as an uncomfortable grocer looked on, the dashing and mysterious new arrival from Canada appeared in the doorway of the market. According to Marianne, he was in a sort of silhouette, with the sun shining behind him, and was wearing a tweeded flat cap. “Would you like to come join us? Come out in the sun. We are sitting outside” he said to her. She’d go on to say, “When my eyes met his, I could feel it through my body.” Marianne dried her tears and agreed and spent the afternoon with Cohen and his companions, talking about art, culture and life. That afternoon a romance began which would inspire some of Leonard Cohen’s most celebrated works and create a lifetime of love.

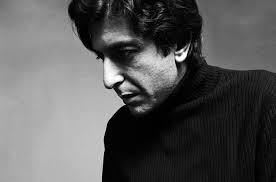

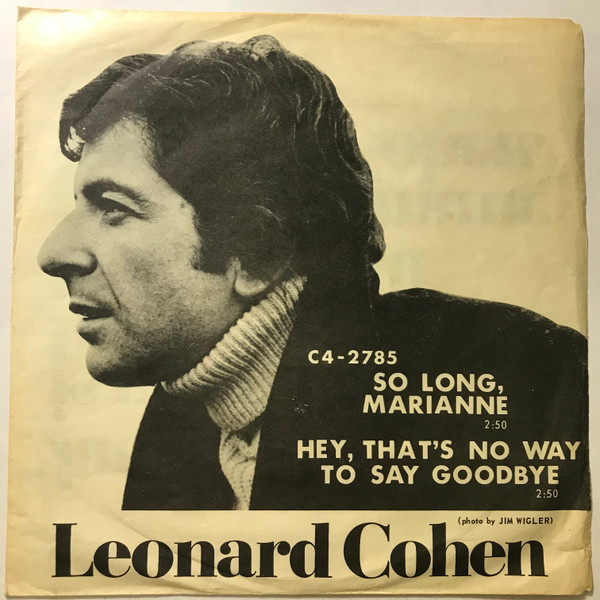

Leonard Cohen is known for his reputation of being a Bohemian sex symbol, and a dashing ladies’ man. Yet despite being romantically involved with many women over his lifetime, he was never married, and didn’t get tied to one woman. But if one woman came closest to tying him down domestically, it’d arguably be Marianne Ihlen. Immortalized in his song “So Long, Marianne,” from his 1989 debut album “The Songs of Leonard Cohen,” he described her hold on him by stating “I’m standing on a ledge, and your fine spiderweb, is fastening my ankle to a stone.”

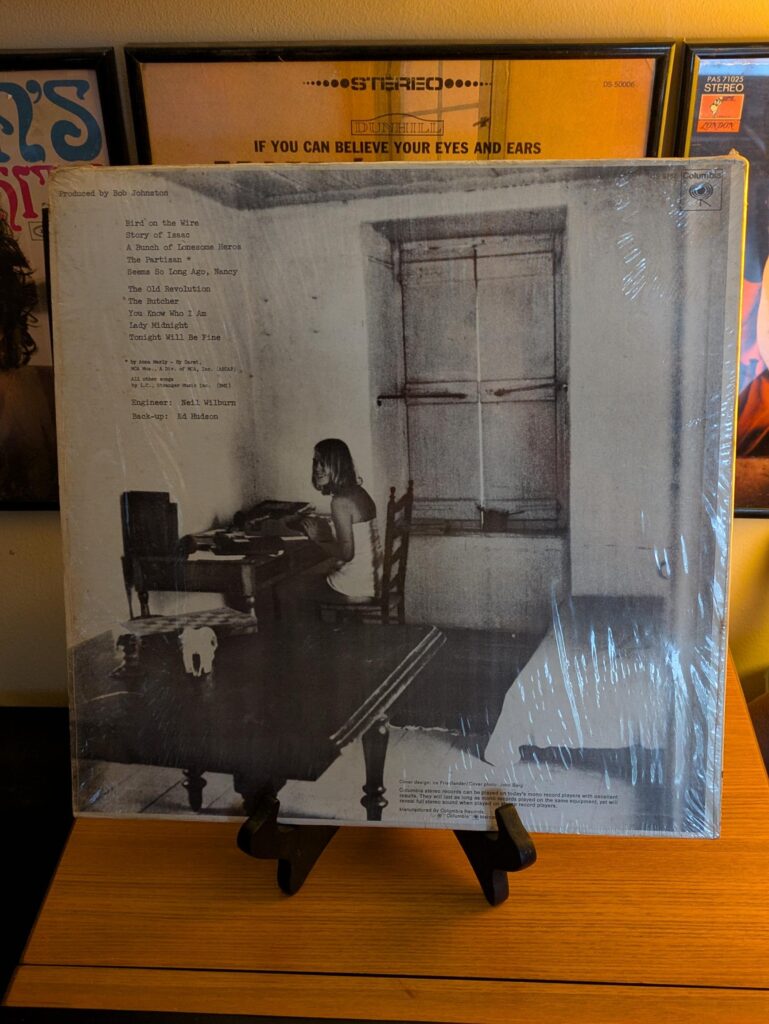

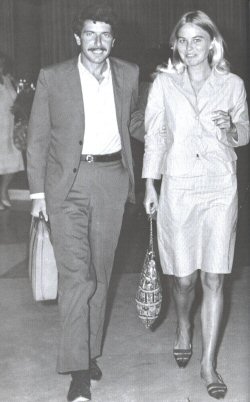

Casual Leonard Cohen fans obviously recognize her name from the famous song, which incidentally is my absolute favorite of all hiscompositions. But shrewder Leonard Cohen fans might know her as the blonde woman pictured on the back cover of his 1969 album “Songs from a Room.” Sitting in front of his typewriter, it’s a grainy photo of Cohen’s work area from his home on Hydra, where he wrote many of his earliest celebrated works. The photo forever freezes in time an important moment in time of Cohen’s most formative era like a black and white fantasy. Along with the desk and the typewriter, Marianne is the third element which helped Cohen become the beloved wordsmith he’d become. However, that fantasy would be only a moment in time, and while the pair tried in vain to continue their romance beyond Hydra, it never seemed to be able to flourish without the sun and the water of Greece to nurture it.

Over the past number of weeks, I’ve thrown myself into the story of Leonard and Marianne, not only through articles and interviews, but also via filmmaker Nick Broomfield’s remarkable documentary “Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love,” which is free for streaming on Plex. Although there is an abundance of information and stories about their life together, sometimes the outline of their movements, both apart and together, is hard to map. Separated between two continents for long periods of time, both Leonard and Marianne spent nearly as much time apart as they did together. Whether traveling through Europe together, as well as multiple attempts to build a new life together outside of the confines of Hydra, their movements throughout North America and Europe seemed constant, and to create a story of substance which would include all their moments would need an entire book. For those who know the story intimately, I might miss one of their destinations or separations, but I’d much rather create a narrative about the key points of their story than create a concrete geographical outline of their entire life together.

But out of all the places which Leonard and Marianne went, the most important place was the Island of Hydra, which was the magical land where their love was born, and where it would forever flourish.

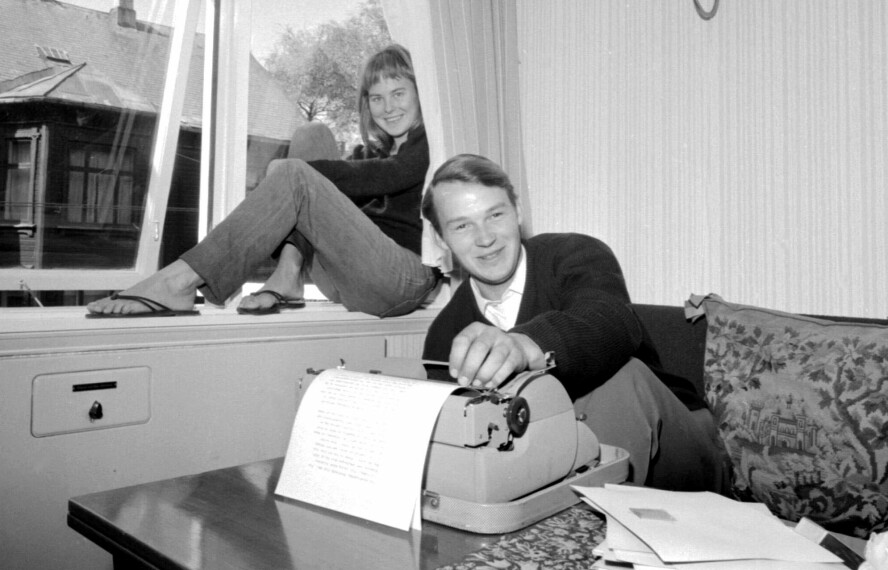

Marianne first arrived in Hydra in 1958 as the newly wed wife of experimental writer Axel Jensen. Despite the objections of her family, Marianne had left with Jensen from their home in Norway to try to make a new life in Greece, but even before they left the relationship was already a tumultuous one. An explosive drunk with bouts of depression and violent outbursts, Jansen had already left Marianne once before and had a long history of infidelity. But soon after getting married in Athens, the couple learnt of an artist colony that had sprouted up on Hydra.

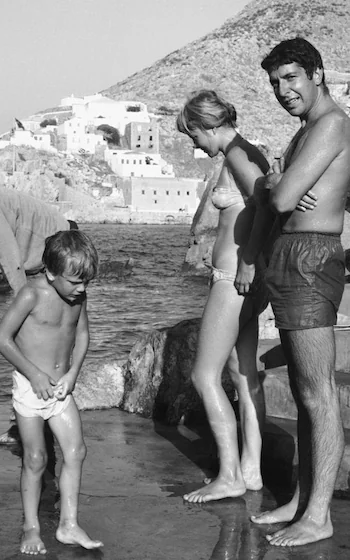

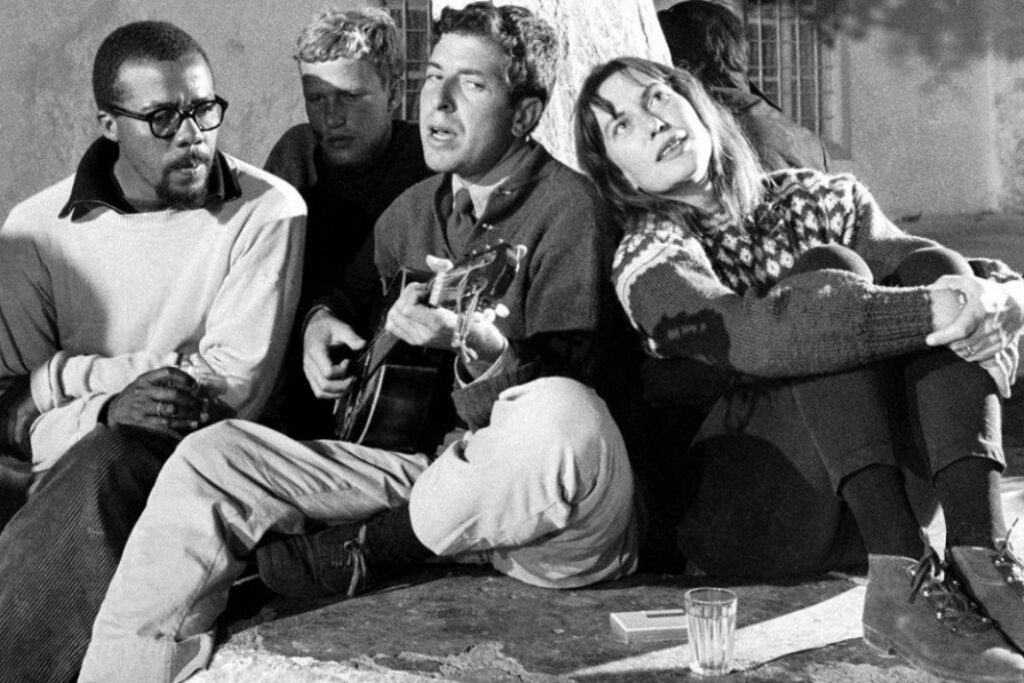

A virtual old world paradise which seemed untouched by time, Hydra was a place where people could escape their reality and commit to their work. A utopia of sea, sun and sand proved to be a place where creatives could get lost in their art, whether that meant hiding while they created, or finding a community with their other unorthodox free thinking neighbors. However, Marianne and Jensen’s time in Hydra would prove short. With Marianne pregnant with their child, Jensen took off one night along for Athens, revealing to Marianne he had met another woman. Although she had managed to become a part of the artist community on Hydra, Marianne found herself heartbroken and alone, with nobody to help raise her yet to be born child.

Meanwhile, Leonard Cohen first arrived in Europe in 1959. A recent graduate from McGill University, Cohen had already established himself as a notable literary figure in Canada, and with a grant from the Canadian council, alongside money left to him by his father, Cohen initially went to London, to pursue a full time career as a writer. However, soon after his arrival, Cohen learnt of the artist colony in Hydra, and longing for the sun and fair weather, he departed for Greece.

Upon arriving on Hydra, Cohen had apparently noticed Marianne and her newborn son, who she had named Axel after her father, around the village and had made inquiries about her. Although he had respectfully kept his distance at first, after he found her crying at the market, the two quickly fell into a deep romance. With money left to him by his recently deceased grandmother, Cohen bought a small house on the Island for a thousand dollars, while Marianne lived nearby at the home she had shared with Jansen. Between writing poetry, Cohen and Marianne became a fixture in the community where they could be seen walking along the beach in the morning or drinking with other artist friends at night. With Cohen stepping up to become a surrogate father figure to little Axel, the pair got swept away in their own little reality, filled with sun, sex and drugs. For three years Cohen and Marianne created a memory of a blissful existence, which they would cling onto when things eventually changed. The imprint of their first few years together would be strongly imprinted on their memories, making their relationship already mythical before it even came to an end.

Cohen and Marianne’s first major separation from one another came in 1961; Cohen to go back to Montreal, while Marianne headed to Norway to reunite with her family. Both renting out their homes in Hydra, the separation from one another would be bitter and emotionally painful for them.

After a few months apart, Cohen sent Marianne a telegram that dramatically read “Have house. All I need now is my woman and her son. Love Leonard.” Longing to reunite with the man she loved, Marianne packed up Axel and the two of them made their first trip to North America. However, the often cold and urban setting of Quebec proved to be a far more challenging existence for the three of them than the ecstasy they experience in Hydra. Suffering a language and cultural barrier with no friends or community of her own, Marianne felt isolated, while Axel proved to be an unhappy child. The small family’s time in Montreal would be fleeting, and in an attempt to regain their happiness and a sense of normalcy, they abandoned Montreal and headed back to Hydra.

Now moving in with Cohen in his small house, Marianne settled in as the keeper of the home while Cohen began his first novel, “The Favorite Game.” Cohen had a strict regime of writing three pages a day, while Marianne kept the household functioning, as well as reminding Cohen to feed and hydrate himself. Through this time, the two had a functional existence, depending on one another for both happiness and survival. But, when Cohen completed his book two years later, he was back in Montreal to have it published. Marianne went back to Norway and, leaving Axel with her mother, relocated to Paris. But after a short period of time, Cohen and Marianne would reunite in Hydra once again to resume their life. These coming and goings would continue and become more frequent, which is one of the reasons while the timeline of their relationship gets so muddy.

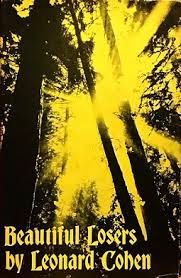

But Cohen’s period between 1964 and 1965 would prove to not only be his most important and intense, but it’d be where imprints of Marianne’s influence on his work would come into play. Cohen’s next project was his second novel “Beautiful Losers,” and Marianne resumed her role as a housewife and lover. But Cohen’s mood had changed, and by partaking on a darker story of sex, betrayal and loss, Cohen fell into a deep state of depression. He also became increasingly dependent on taking acid as a way to maintain his creativity, which pretty much explains everything when reading “Beautiful Losers.”

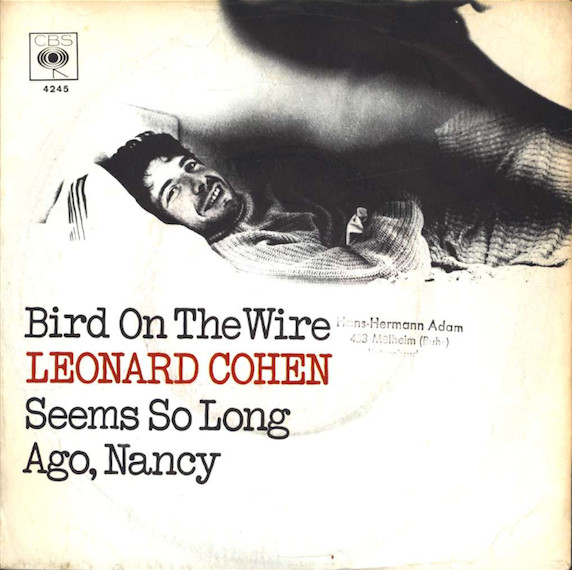

Often suffering of anxiety when the words wouldn’t flow, Cohen’s depression worsened until he hit a devastating period of writer’s block. Deciding that the problem was environmental instead of emotional, in frustration Cohen told Marianne that they were going to get rid of the house and move. Figuring that Cohen was being too extreme, Marianne looked out the window and noticed three black birds sitting on an electrical wire nearby. Electricity was, for the first time ever, coming to Hydra, and birds sitting on wires was a new site. Marianne pointed this out to Cohen and said “Look at the birds. They look like musical notes. Write about that.”

Inspired by Marianne’s keen observation, Cohen sat at his typewriter and wrote one of his most famous compositions, “Bird on a Wire.”

“Like a bird on the wire

Like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free

Like a worm on a hook

Like a knight from some old fashioned book

I have saved all my ribbons for thee

If I, if I have been unkind

I hope that you can just let it go by

If I, if I have been untrue

I hope you know it was never to you.”

The next few years would be a blur of drugs and depression, but Cohen finally finished “Beautiful Losers” in 1965, but by then, the relationship between Marianne and Cohen had started to become strained. The fairytale romance of their early days on Hydra had seemed to have eroded, and the relationship became far more volatile, Yet, even as things began to break down, the pair held on to the memories of their early days, and a desire to return to that time in their life. The emotional roller coaster of their relationship was forever chronicled in a piece of poetry that Cohen titled “Come On Marianne,” where he beautifully encapsuled their relationship trauma, which eventually would form an intimate portrait of their eroding relationship that the world would eventually come to embrace:

“Come over to the window, my little darling

I’d like to try to read your palm

I used to think I was some kind of Gypsy boy

Before I let you take me home

Come on, Marianne

It’s time we began

To laugh and cry and cry

And laugh about it all again

We met when we were almost young

deep in the green lilac park.

You held on to me like I was a crucifix,

as we went kneeling through the dark.

Your letters they all say that you’re beside me now.

Then why do I feel alone?

I’m standing on a ledge and your fine spider web

is fastening my ankle to a stone.

For now, I need your hidden love.

I’m cold as a new razor blade.

You left when I told you I was curious,

I never said that I was brave.

Oh, you are really such a pretty one.

I see you’ve gone and changed your name again.

And just when I climbed this whole mountainside,

to wash my eyelids in the rain!

Come on, Marianne

It’s time we began

To laugh and cry and cry

And laugh about it all again.”

As Cohen’s travels between Montreal and Europe began to rapidly increase, the times that the couple spent together went from years, to months, to only weeks. This caused another set of anxieties within the relationship, as Marianne desired a functional domestic situation, while Cohen was beginning to get the wanderlust he always had. Furthermore, it was later observed by people who know him that Cohen had a quality about him which never allowed him to completely give himself to any one person. He loved the idea of love and commitment, but the moment he had it he’d run from it. As Cohen’s travels increased, Marianne’s loneliness also began to show itself, especially with Axcel now tucket away at boarding schools. Marianne’s separation trauma would go on to inspire another of Cohen’s most beloved compositions, “Hey That’s No Way to Say Goodbye”:

“I loved you in the morning, our kisses deep and warm

Your hair upon the pillow like a sleepy golden storm

Yes, many loved before us, I know that we are not new

In city and in forest they smiled like me and you

But now it’s come to distances and both of us must try

Your eyes are soft with sorrow

Hey, that’s no way to say goodbye

I‘m not looking for another as I wander in my time

Walk me to the corner, our steps will always rhyme

You know my love goes with you as your love stays with me

It’s just the way it changes, like the shoreline and the sea

But let’s not talk of love or chains and things we can’t untie

Your eyes are soft with sorrow

Hey, that’s no way to say goodbye.”

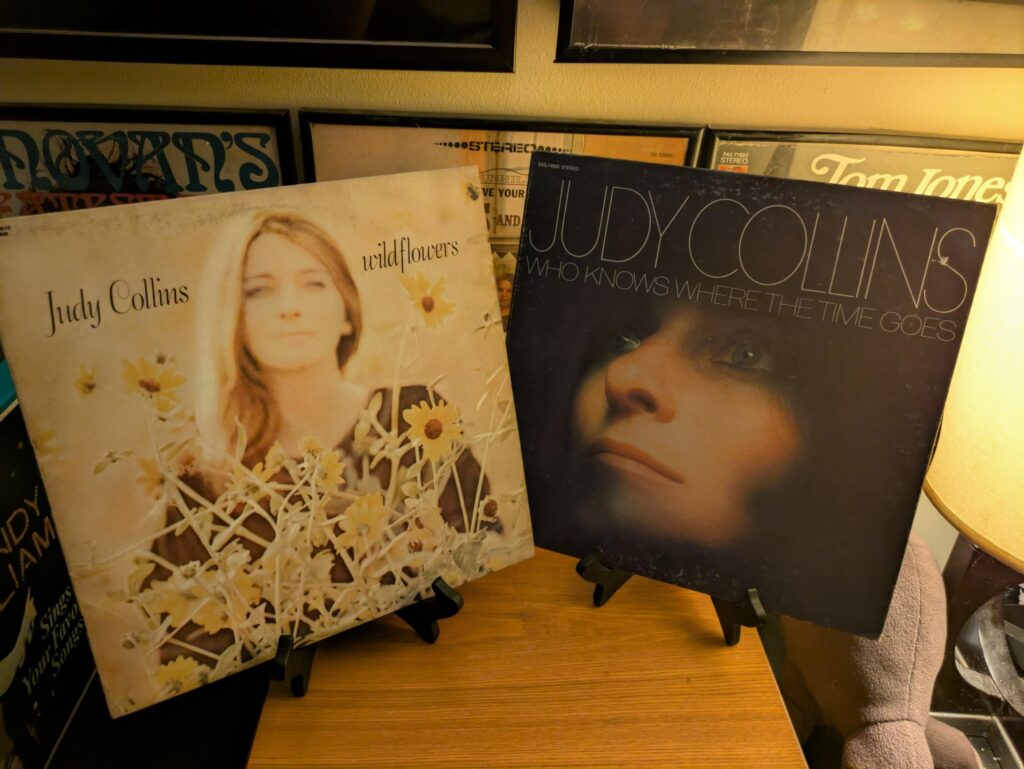

It’d be Cohen’s departure to Montreal in 1965 to publish “Beautiful Losers” which would be the bitter turning point in Cohen and Marianne’s life together. After divisive reactions to “Beautiful Losers,” Cohen came to the realization that he could not maintain a living as a writer, and he turned his attention to music which led to his relocation to New York City and, eventually, his friendship and collaborations with Judy Collins (for a comprehensive narrative on these events, read my Vinyl Story Leonard Cohen – The Songs of Leonard Cohen (1968z”). After the success of her 1967 album “In My Life,” which featured “Suzanne” and “Dress Rehearsal Rag,” Judy continued to debut Cohen’s newest compositions on her albums. For her follow up album, “Wildflowers” (1967), Judy recorded the first version of “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” and on 1968’s “Who Knows Where the Time Goes,” she became the first of many artists to record “Bird on a Wire.”

Although Cohen sent Marianne money for her life on Hydra, as well as for Axel’s schooling, Marianne was lonely, unhappy and dejected/ This time Cohen and Marianne had left their relationship open ended, allowing both of them to take on other lovers. But, longing for her life with Cohen, in 1966 she made the decision to follow him to New York City. This would prove to be the death toll on their relationship. Not wanting Marianne in New York, Cohen set her up in an apartment in Greenwich Village while he maintained his separate life at the Chelea Hotel. Although he took her around to meet new associates like Joan Baez, Richie Havens and Andy Warhol, there was an undeniable distance between the pair. As Cohen’s career began to flourish, Marianne began to see their life in Hydra coming to an end and began to resent all the factors for Cohen’s success. According to Judy Collins, in an interview for Nick Bromfield’s documentary, one night Marianne confronted her by stating, “You made Leonard Cohen a success, but you destroyed my life.”

Cohen claimed that the reason that he didn’t want Marianne in New York was that he didn’t want her to be tainted by the grit of his newfound lifestyle. However, Cohen had entered a new relationship with a young artist named Suzanne Elrod. Not to be confused with Suzanne Virdal, the Montreal based dancer who was the subject of his song “Suzanne,” there are varying stories on just how Cohen met Elrod. One story sees her as a nineteen-year-old girl who he met on an elevator and asked to coffee. Another says she was 24 and that they met when Cohen was brought to a Scientology center by an associate. Transparent with both Marianne and Suzanne about the situation, and unwilling to let either of them go, for a time the three of them lived in an uneasy triangular situation. But, while Marianne was docile in her hold on Cohen, allowing him to drift in and out of her life despite hating to be without him, Suanne was far more aggressive, and dug her claws deeper to hold on.

But the writing was truly on the wall when Leonard Cohen released “Songs of Leonard Cohen” in 1968, and Marianne saw the very notable change to the poem that he had immortalized their relationship in. Now a song itself, “Come On Marianne” was retitled “So Long, Marianne.” Not initially written as a farewell piece, Marianne finally realized she was just existing in a space she was not wanted, and packing up her belongings, she retreated to the little house in Hydra.

For a while Cohen attempted to support both women, financially and emotionally, returning from time to time to Hydra to be with Marianne, while building a new life in New York with Suzanne. But the final death blow for the relationship came in early 1973 when Suzanne showed up in Hydra on Marianne’s doorstep holding her and Cohen’s new infant son Adam. Taking claim to what she deemed Cohen’s property, she asked Marianne when she planned to move out. With Cohen now starting a family with Suzanne, Marianne felt there was no longer any future for them, and she packed up her things and moved back to her family in Norway.

In the years to come, Marianne settled in Oslo and began to work at a company called Norwegian Contractors, where she met an engineer named Jan Kielland Stang and they eventually were married. Finally finding the domestic life she longed for; Marianne and Jan had three daughters together. Marianne lived quietly, with her life in Hydra slipping into the past.

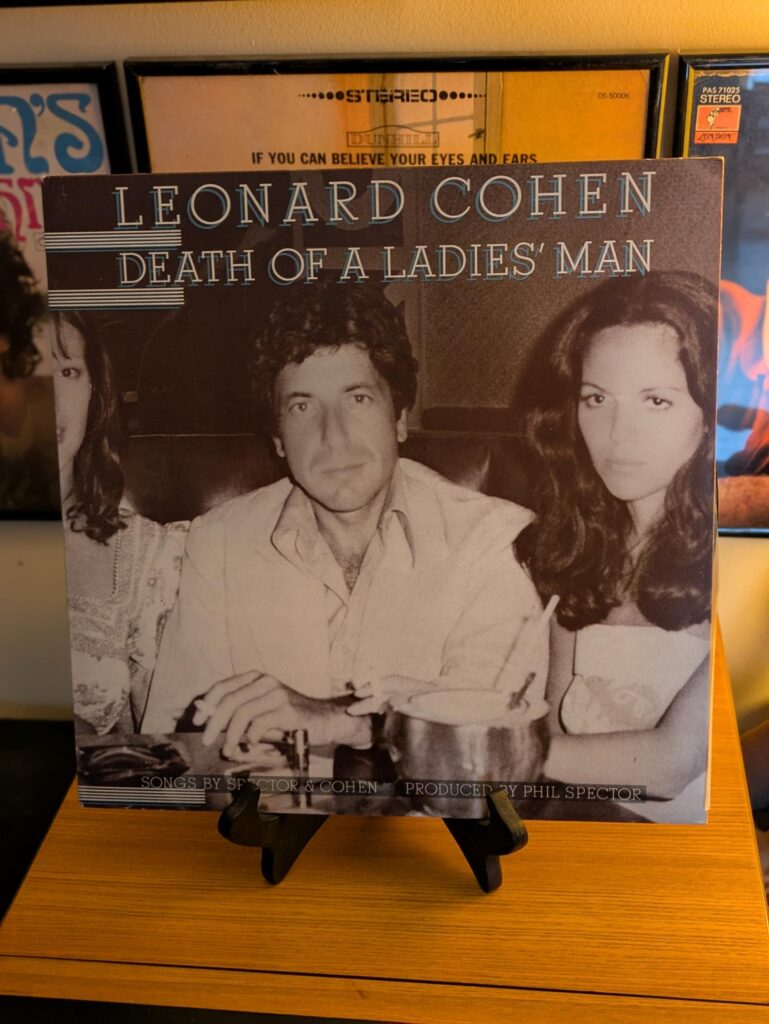

Meanwhile, Cohen and Suzanne Elrod would have a second child, Lorca, but Cohen never married her. With Suzanne’s far stronger personality, the relationship was often confrontational, and began to break down during the chaotic production of “Death of a Ladie’s Man,” Cohen’s disastrous project with Phil Spector, released in 1977 (ironically, Elrod appears as the woman on Leonard Cohen’s right on the album cover). Suzanne would leave Leonard Cohen in 1978.

But despite the bitterness at the end of their relationship, Cohen and Marianne maintained a friendship for the rest of their lives. Whenever he was performing in a Scandinavian country, he’d send Marianne tickets and transportation for the show, and he would meet with her and her family for visits thereafter. Speaking of each other in the media countless of times, both Marianne and Cohen only spoke of one another with respect and love.

But this is not the end of this narrative. There would be one final act of love in their story.

In 2016, at age 81, Marianne was diagnosed with leukemia and her health rapidly declined. Committed to palliative care, Marianne knew that the end of her life was upon her, and she contacted her friend Jan Chrisitan Mollestad to ask him to contact Cohen and let him know that she was dying. Mollestad did as she requested, and a few days later Marianne released the following email from her former lover:

“Dearest Marianne,

I’m just a little behind you, close enough to take your hand. This old body has given up, just as yours has too. I’ve never forgotten your love and your beauty. But you know that. I don’t have to say any more. Safe travels old friend. See you down the road. Endless love and gratitude.

Your Leonard”

Marianne passed away days later on July 29th, 2016. Months later, on November 7, 2016, Leonard Cohen died at age 82 in his home in Los Angeles. It was as if he had kept his promise to travel with her down the road, rejuvenated forever as if they were back on Hydra during the early days of their love.

One final studio album, “Thanks for the Dance” was released in 2019 when Adam Cohen finished production of a number of recordings from songs that were left over from Cohen’s last album “You Want it Darker?” (2016). Amongst the tracks completed by Adam was one final song Leonard Cohen had written about Marianne. Titled “Moving On,” it was one final tribute to Marianne from beyond the grave:

“I loved your face, I loved your hair

Your T-shirts and your evening wear

As for the world, the job, the war

I ditched them all to love you more.

And now you’re gone, now you’re gone

As if there ever was you

Who broke the heart and made it new

Who’s moving on?

Who’s kidding who?

I loved your moods, I loved the way

They threatened every single day

Your beauty ruled me, though I knew

‘Twas more hormonal than the view.

Now you’re gone, now you’re gone

As if there ever was you

Queen of lilac, Queen of blue

Who’s moving on?

Who’s kidding who?”

Although their time seemed fleeting on Hydra, Leonard Cohen and Marianne Ihlen lived a lifetime of love, which the entire world would feel in the passion and the music of some of Cohen’s most beloved songs. Entangling their love once more in their final days, Leonard and Marianne are finally forever together in song, walking hand and hand for eternity.