April 30, 1967, would prove to be a historic date in Paul Revere and the Raiders’ history. At the height of their popularity, it was the night that the group were to make their first, and only, appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” However, unbeknownst to the fans who watched at home, it was also the official end of the first golden era of the group. With four top 20 hits on the Billboard charts in under just two years and having become household names after their successful run as regulars on Dick Clark’s “Where the Action Is,” The Raiders were one of the biggest rock bands in America. But beyond the smiles and zany antics, there was great turmoil behind the scenes and just weeks before the band’s entire backline, comprised of Drake Levin on guitar, Phil “Fang” Volk on bass and Mike “Smitty” Smith on drums, had told band leader Paul Revere that their “Ed Sullivan” appearance would be their last. When they got to The Ed Sullivan Theatre that night for the ‘big show,’ Paul let them know that as far as he was concerned, they were expendable and he already had a new guitarist filling in for Drake for the broadcast. With no mention to the audience of the drama that was unfolding behind the scenes, Volk and Smith performed their final performance while Drake watched from the wings. After the show, Mark Lindsay and Paul Revere were left to look for more replacements for their once dynamic group, while Volk, Smith and Levin were on a new rock’ n roll journey as Brotherhood.

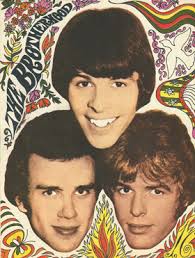

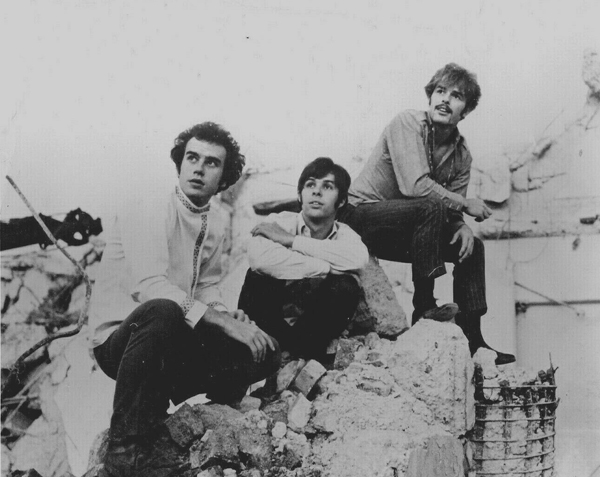

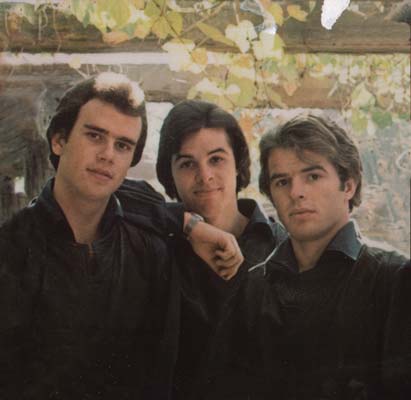

Have you ever heard of Brotherhood? Don’t worry if you haven’t. Although I’ve been obsessed with Paul Revere and the Raiders for years, it’s only recently even heard of Brotherhood myself. It’s not a group that anybody ever seemed to have been talking about, and despite high ambitions by three incredible showmen, the group became little more than an obscure footnote from the 1960’s. But after their stormy departure from The Raiders, popular fan favorites Drake Levin, Phil Volk and Mike Smith hung up their three cornered hats and formed the group in an attempt to break out from the shadow of Mark Lindsay and Paul Revere and bring their own musical ideas to life. Filled with high aspirations and proven talent, Brotherhood had promise but never seemed to get the support they needed to allow them to succeed. As a result, most people haven’t even heard of Brotherhood. Not then, and not now.

So, when I learnt about Brotherhood earlier this year, my mind was blown that a Raiders splinter group made up of three of the most important players in the band’s history even existed, and I raced down that rabbit hole to learn more! Having never seen a Brotherhood album in any music shop or record show (at least to my recollection) I wasn’t willing to “crate dive” for possibly years to find one of their albums, so I turned to Discogs so I could get their 1968 self-titled debut album immediately. Although Brotherhood albums seem to be rare, they are out there at a reasonable price, and when the album came in the mail a week later, I was excited to nosedive into the further musical exploits of Levin, Volk and Smith.

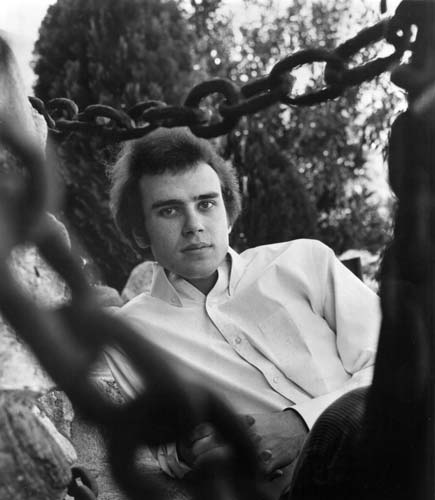

So why did Levin, Volk and Smith leave The Raiders at the height of the group’s popularity? I covered all of those details in my Vinyl Story “Paul Revere and the Raiders – Greatest Hits (1967),” but to summarize the split, the three young performers left over their dissatisfaction with the direction The Raiders were going in. As the group became more popular, increased outside control began to have a greater say in the material the group was creating, and in an effort to keep the band both commercial and popular with a young audience, The Raiders were told to stay non-political and irrelevant. Furthermore, as lead singer Mark Lindsay formed a tight bond with producer Terry Melcher, the other Raiders started to feel less relevant to the group, with Melcher turning down songs that Levin and Volk had written, and eventually hiring The Wrecking Crew to overplay them on “The Spirit of ’67.” All under the age of 25, Levin, Volk and Smith had music they wanted to make, and things they wanted to say, and they felt boxed in as Raiders. So, just before the release of what would prove to be their best album, they left to pursue their own musical path.

But their revolt from The Raiders would come with crippling fallout that kneecapped them, delaying their progress in a rapidly changing music scene. Angry over their departure, Paul Revere immediately sued Levin, Volk and Smith for “breach of contract,” which was joined by a similar lawsuit filed by their label, Columbia Records. Meanwhile, a third law suite was filed by music manager Allen Kline over a convoluted matter with Kline accusing the trio of unpaid money. To make matters even more dire, Columbia Records still had Levin, Volk and Smith under contract and were refusing to release them, preventing them from signing a recording deal with anyone else, and their money from their final Raiders tour was frozen, leaving them with no money to live on, let alone start a new project with. So as Mark Lindsay and Paul Revere began to reassemble The Raiders with new members, Levin, Volk and Smith found themselves broke and drowning in litigation.

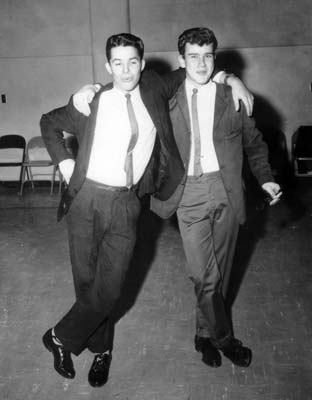

Yet while discouraged, it couldn’t take away their musical ambitions. Having been writing together since they were in high school, Levin and Volk continued to create new music together, and after years of performing with Smith, they were still a well-oiled unit. Initially they planned to call themselves simply “Levin, Volk and Smith,” but feeling that they were tied to each other, they redefined their personal relationship by calling themselves Brotherhood. It should also be noted that they dropped their Raiders monikers “The Kid,” “Fang” and “Smitty,” so as difficult as it is for me, I’ve dropped those names for this narrative as well.

Although temporarily paralyzed due to the legal restrictions brought upon them, Levin, Volk and Smith still needed to work, so they began to look up their old friends for help. Dick Clark was a benevolent supporter, but without an album on the market, he wasn’t willing to give them coverage on “American Bandstand.” “16 Magazine’s” Gloria Stavers was a lot harsher, willing to give an occasional quote or update on the ex-Raiders’ current activities in the news or gossip sections, but she was far more interested in promoting and spotlighting the exciting “new Raiders.” Gloria’s editorial mandate was to focus on the celebrities that the readership wrote in to her about, and with the former Raiders out of the limelight, Gloria wasn’t going to give them the spotlight.

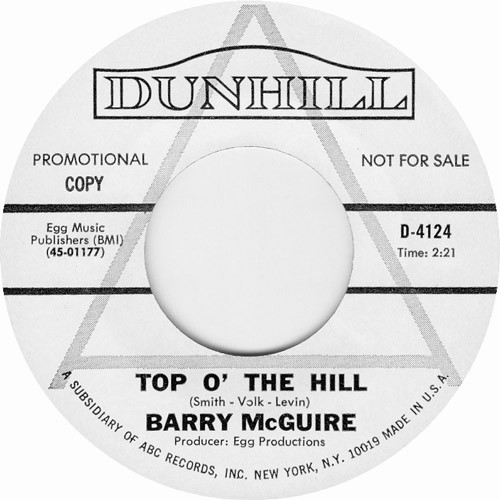

But Brotherhood would find a surprising early ally in record producer Terry Melcher. Although he was instrumental in creating the schism between the members of Brotherhood and their former Raiders bandmates, Melcher hired them as session musicians for projects he was working on, and even bought two songs off of them for Barry McGuire to record for his 1968 album “The World’s Last Private Citizen,” – “The Grasshopper Song,” and the album’s single “Top O’ the Hill.”

After a difficult year of feeling defeated at every corner, in early 1968 Levin, Volk and Smith took a much needed retreat to Hawaii to refresh, regroup and do some soul searching. After a number of weeks driving across the Island together, the group returned to Los Angeles and recommitted themselves to sorting out the lawsuits and finally making Brotherhood a reality.

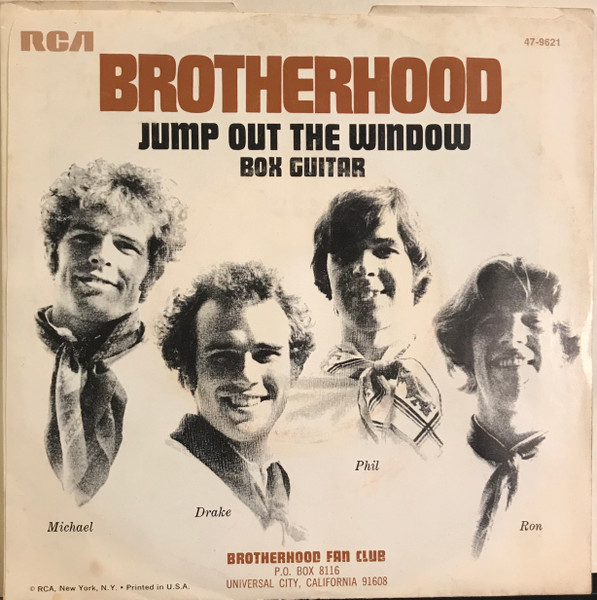

Renting space at a small recording studio in Hollywood, Levin, Volk and Smith finally began laying down some new material and added keyboardist Ron Collins to their lineup. A guy that Levin knew, Collins never seemed to endear himself to the rest of the group and was described as being “quiet” and “odd.” But if Revere could replace them on guitar and drums, why couldn’t they replace Revere on keys?

With Levin and Volk taking lead vocals, Brotherhood was able to prepare a series of recordings for RCA Records, who signed them to a contract for a three record deal. It really seemed like a no brainer for RCA. Brotherhood was made up of guys that had already proven themselves to be excellent musicians, and in theory should have a built in fanbase due to years of coverage in the fan magazines. Given the freedom to do what they needed, for the first time ever Levin, Volk and Smith were able to bring their own music to life. However, too much freedom and a ton of pent up ambition would prove to be their eventual downfall.

With the recent release of The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” like nearly every working band in the world at that moment, Brotherhood was inspired by the Fab Four’s psychedelic masterpiece and sought to make an album like that. However, as good as The Raiders ever were, they were never The Beatles, and in creating their debut album, Brotherhood lacked the know how to make another “Sgt. Pepper.” But that did not deter them, and when writing the material for the album, Levin, Volk and Smith reached far beyond what they had done before to write different types of songs and overextended themselves in terms of production. As a result, it took eight months to complete the album, and much to RCA’s disapproval, went way over budget.

But the pressure of making the album began to put a strain on the members of the band. Believing his entire career was hinging on this one record, Levin, who could be a perfectionist, was putting a ton of pressure on himself in creating the album. As a result, daily arguments broke out between him and Volk about nearly every detail in both production and the band’s business. One of the most divisive issues between Levin and Volk was the subject of live performances and touring. Levin wanted to hit the road and do multi-city tours, just as they had in The Raiders days, but remembering how the constant touring affected his emotional and physical health, Volk wanted to stick to the Los Angeles area and do nothing but local gigs for the time being. Yet, as frequent as the fights between them were, the constant bickering didn’t seem to affect their friendship or respect for one another as much as it hindered the productivity of the project. Smith, on the other hand, wisely managed to stay out of the heated arguments, usually walking away from the studio with a shrug and an eyeroll. Ron Collins, on the other hand, was basically treated like a junior member of the band with little say and no creative input. Essentially, Levin and Volk were treating him the same way they were being treated by Terry Melcher and Mark Lindsay, and while he may have been in Brotherhood, he was never really a part of the actual brotherhood.

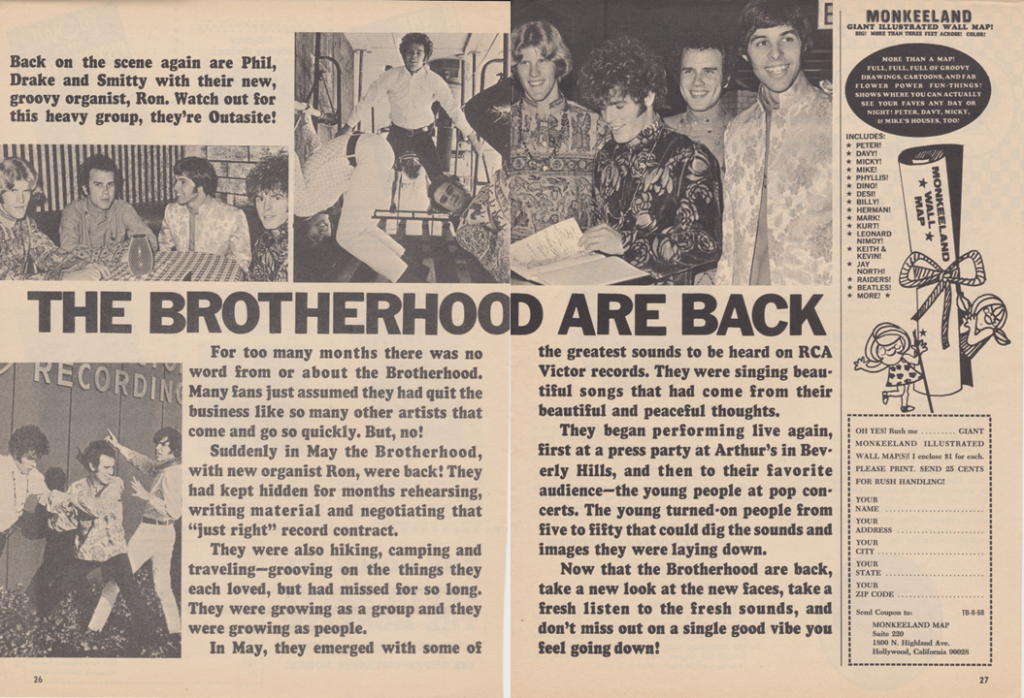

Brotherhood’s self-titled album was finally released by RCA in the summer of 1968, with the first single on the album being “Jump Out the Window.” A psychedelic number that had the same electric elements that the group had brought to The Raiders, even the decision on that became problematic because while it was actually about liberation from the strict confines of The Raiders, Volk wondered if it could be mistaken as an act of suicide, or deemed to be about a hazardous LSD trip gone wrong. But, disenchanted due to the project going over budget, and putting all their energy into promoting The Jefferson Airplane’s latest album, “Crown of Creation,” which was released at the same time, RCA did nearly nothing to promote the album. Instead, Brotherhood was left to promote themselves and, again, contacted their former allies from their Raiders days. As promised, Dick Clark put them on “American Bandstand,” and Gloria Stavers did an obligatory write up on Brotherhood for “16 Magazine.” However, after that it was up to the listeners to give the final say on whether Brotherhood was going to be hot or not, and for the most part they didn’t even know the album existed. Brotherhood was not being played on the radio, not being stocked in the record stores, and not coming to your town. Nothing seemed to be moving for Brotherhood.

Although an ambitious album, “Brotherhood” suffers from being a disjoined album that lacks any sense of cohesion. It was as if the group was so caught up in trying to stretch out stylistically and prove that they were not Raiders anymore, the album never truly came together. Some of the tracks, such as “Somebody” and “Close the Door” contains the raw energy that fans love Levin, Volk and Smitty for, while “Love for Free” was little more than an obvious rip off of The Beatles. Other songs, such as “Lady Faire,” “Pastel Blue” and “Forever” are pretty ballads, showing off a sensitivity to Levin and Volk’s vocal style, and seem to harness the folk energy that was making Donavan popular. However, due to awkward placement within the album, they manage to slow the pace to a near standstill. But possibly hurting the album the most was the fact that it just didn’t have a hit. The memorable hooks that they had with The Raiders were not there, and although Volk and Levin were fine singers in their own right, they lacked the raw front man charisma of Mark Lindsay. As a result, “Brotherhood” was released with little more than a whisper and quickly faded to record store clearance racks, if they even bothered to stock it at all,

But Brotherhood had more music to make, and their next project would be their most experimental and, as a result, their most exciting. In order to keep themselves cohesive and excited about music during the extremely stressful production process on the first album, Levin would often have friends over to his home for wild jam sessions. Usually made up of session musicians, dignitaries such as Jimi Hendrix and David Crosby would often also show up. One night, Levin recorded the festivities and, impressed with the outcome, wrangled the members of Brotherhood together to engage in an experimental free for all of sounds, rhythms and instrumentals that would weave into nowhere. This became the group’s second album, “Joyride.” Sitting somewhere between a Frank Zappa project and John and Yoko’s “Two Virgins,” “Joyride” was way too far out for RCA, who reluctantly agreed to released it as long as the group to put it under another name. The result was the moniker “Friendsound.” A highly experimental piece, “Joyride” is actually surprisingly listenable, and holds up far better than the material on “Brotherhood” does. But, having little faith in the record, RCA basically buried it, and “Joyride” went even more unnoticed and undersold that the group’s debut album. A shame, because I think “Joyride” is the coolest thing that came out by Levin, Volk and Smith during this period of their career, and it’ll probably be my next Discogs purchase.

With the failure of both “Brotherhood” and “Joyride,” the glue that held Brotherhood together finally fully corroded. As the arguments between Levin and Volk continued, Smith decided he had had enough. Having fallen in love with Hawaii during their retreat there, Smith quit the group and headed back to the Islands. Shortly thereafter, Ron Collins, feeling underappreciated and underused, decided he too wanted out and quit. Now Levin and Volk were in the same situation as Paul Revere and Mark Lindsay had been when they left The Raiders, and they were still under contract to make one more album.

On a recommendation from Volk’s younger brother, Seattle based drummer Joe “The Machine” Pollard, who would go on to perform with Etta James, The Grass Roots and The Beach Boys, joined up with Levin and Volk for the third album. With their budget significantly reduced by RCA, who had lost all faith in Brotherhood’s output, the group cobbled together a third album called “Brotherhood, Brotherhood” in only a matter of weeks. The album would consist of a few unrecorded songs, covers of The Beatles “Long Way Home” and Lynne Anderson’s “Rose Garden” performed Vanilla Fudge style, and even a borrowed track from the “Joyride” album. “Brotherhood, Brotherhood” was released in late 1969 with, once again, no promotion. Although RCA was putting nearly no resources into supporting the group, a promotional single of “Don’t Let Go” was sent only to radio stations, but not into stores, and when it received no support, RCA all but abandoned Brotherhood and ended their contract. Defeated, broke and with their solo dreams finally shattered, as the 60’s morphed into the 1970’s, Levin and Volk called it quits, and Brotherhood was finished.

But in the years to come, the members of Brotherhood managed to find their way back into the music scene. In 1971, after his replacement Joe Correro left The Raiders, Mike Smith rejoined the group for a short time, touring with them to promote their first and only #1 hit “Indian Reservation,” and played on 1972’s “Country Wine,” which was The Raiders’ final album with Mark Lindsay. Shortley after Brotherhood dissolved, Phil Volk joined up with Rick Nelson and became the bassist for his touring band, before he and his wife, former “Action Kid” Tina Mason, formed their own group, The Friendship Train, and had a long standing gig at Disneyland from 1975 to 1980. Drake Levin would go to do some further session and production work, and eventually opened his own guitar store, called Drake’s Guitars, on Hermosa Beach.

But the Brotherhood would come together again, and Levin, Volk and Smith would find themselves beside each other as bandmates on a few special occasions. The first was for a 1979 special called “The Good Ol’ Days,” where former mentor Dick Clark managed to reunite the trio with Mark Lindsay and Paul Revere for one performance only. Donning their old Raiders uniforms and performing to a star studded audience, the original Raiders did a medley of hits including “Steppin Out,” “Kicks,” “Hungry,” and “Good Thing.” Despite not having played together in twelve years, the five of them were still hot together. Volk performed on his old base with “Fang” spelled out in electrical tape on the back, he and Levin were once again in perfect step with their synchronized dancing, Smith was keeping the beat and Lindsay was oozing raw energy, proving himself as one of the best front men in rock n’ roll. Even Paul Revere was in good form, not doing any asinine unfunny comedy and being unusually chill. The performance was the final time the group would perform all together, and the audience launched into a well-received standing ovation. Volk, Smith and Levin would come together three more times. The first was in 1997 in Portland, Oregon where they performed one last time with Maek Lindsay, and they did another pair of shows in Hayward, California in 1998 as a trio..

Mike Smith passed away from undisclosed reasons on March 6, 2001, and Drake Levin died after a battle with cancer on July 4, 2008. Of all the members of the group, Levin was said to be the one who had the most difficulty getting over Brotherhood. He deemed it the biggest failure of his career, and the rock n’ roll dream that didn’t come true. Apparently he never talked about Brotherhood, nor revisited their albums. However, weeks before his death, after a visit from Phil Volk to say goodbye to his old friend, Drake apparently sang a song to his wife Sandra which she had never heard before. That song was from Brotherhood’s debut album and was “Forever.” The lyrics of “Forever” would go on to be printed on the program at Drake’s memorial service:

I knew you before,

I’ll know you again,

And the love that we give,

For as long as live,

I believe in Forever.

Remember tomorrow,

I still see the past,

And the love never fades,

Though time slips away,

I believe in Forever.

Meet you on the other side of forever,

Treat you to a drop of sunshine mellow

To brighten your sorrow,

The other side of Forever

The sand on the beach,

The sand in the glass

The dust in my veins,

Will be dust again,

I believe in Forever

What went wrong for Brotherhood? Why did history forget them, and why wasn’t the band successful for Drake Levin, Phil Volk and Mike Smith? Who can really say for sure. Some of the most deserving musicians don’t receive the success that they probably deserve. But in the case of Brotherhood, perhaps it was a matter of too much ambition with too little support from the label and the press, which prevented the fans from even knowing that the former Raiders even had a record out at all. In all honesty, “Brotherhood” is a decent album, and you can hear the talent of the players in every track, but it just never took off the way that maybe it should have. Brotherhood deserved more of a chance to grow and explore their musical path, but time just seemed to have run out.

VINYL STORY NOTE: When researching this story, much of the information I used was from writer Bill Kopp’s comprehensible history of Brotherhood, “Jump Out the Window: The Brotherhood Story,” which was compiled in a ten part series for “Ugly Things Magazine” and is readily available to read at his music blog, Musiccribe.com. A brilliantly researched and well written piece of music journalism, the series thoroughly details all three of Brotherhood’s albums and has insightful interviews with Phil Volk, Ron Collins, Joe Pollard and many of the people who were close to Brotherhood during the time of their existence. In order to not plagiarize or disrespect the integrity of Kopp’s excellent work, I was careful not to incorporate any of his interview quotes into my write up on the group. With very little about Brotherhood being written, Ron Kopp is easily the authority on Brotherhood, and I’d consider his article the official history of this obscure group. If you want more insight and infromation on Brotherhood, I strongly encourage you to check out “Jump Out the Window: The Brotherhood Story.”