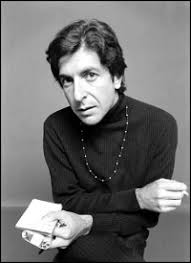

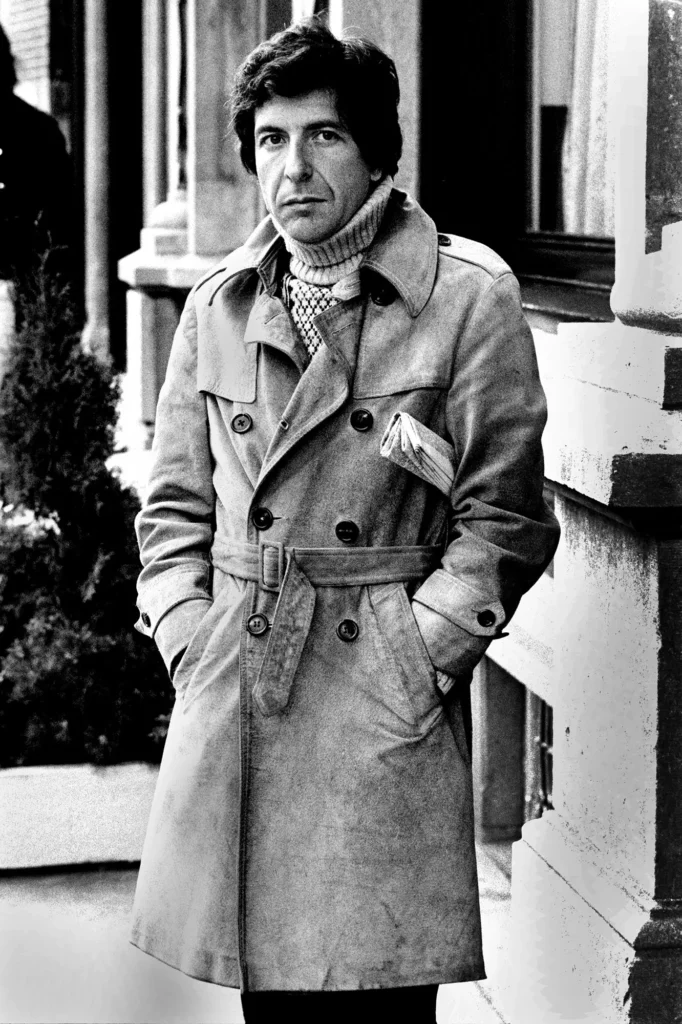

Although it’s been eclipsed by the popularity of “Halleluiah” over the past few decades, when I discovered the music of Leonard Cohen in the early 1990’s, his best known song was “Suzanne.” Seriously. Nobody but the most diehard Leonard Cohen fans knew what “Hallelujah” was before 2007. But “Suzanne” was another story. If you had only the most basic knowledge of who Leonard Cohen was, you at least knew “Suzanne.” For much of his career, Cohen’s music was not as widely known nor celebrated as it is now, and while he had a strong legion of fans amongst both professionals and serious music listeners, the popularity of “Suzanne” as a standard amongst introspective musicians was what initially put Leonard Cohen on the musical map. As the song that launched Leonard Cohen’s music career, he would often credit it as being the best song he had ever written in his long and eventful career.

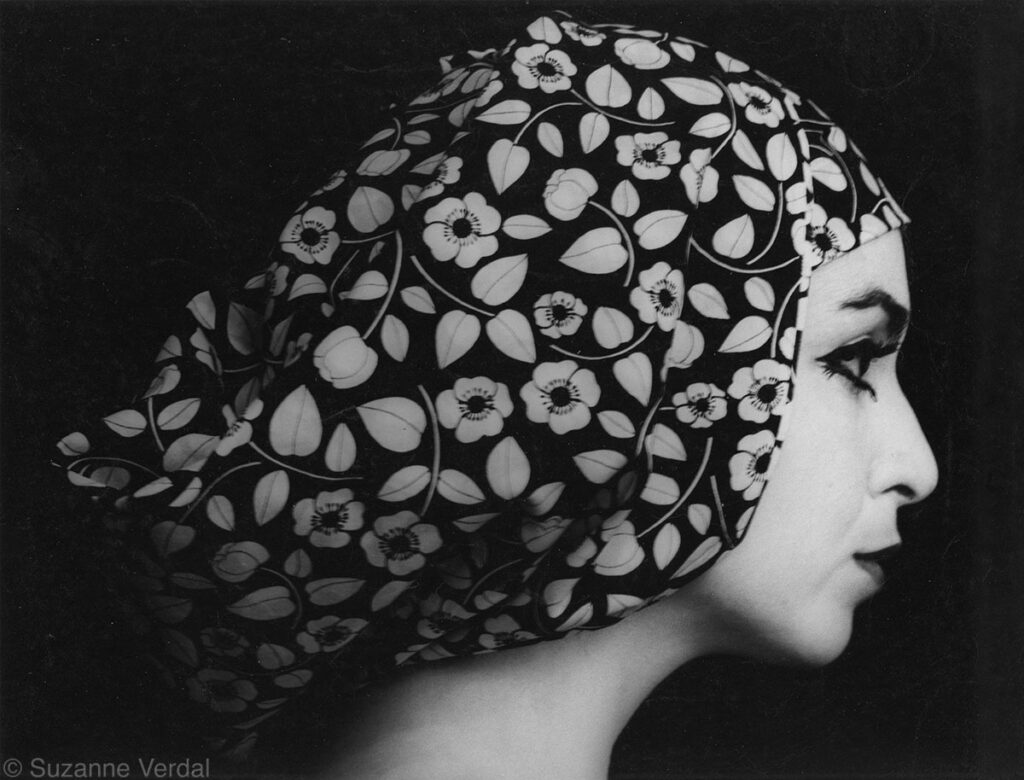

A bohemian love letter to Montreal’s beat culture, “Suzanne” is a tapestry of mystery, mysticism and eroticism filled with sensual imagery and artistic sensitivity as Cohen writes about his strange friendship with the intense and enigmatic Suzanne. Filled with strange imagery and delicate wordplay, it is a song that fills the imagination with romance and wonder, glamorizing the cerebral quietness of the artists and lovers that exist on the fringes of society. However, what might be surprising to listeners is that the lyrics to Suzanne were not nearly as cryptic as they may have ever seemed. There was never any need to untangle any hidden meaning within “Suzanne” because Leonard Cohen was telling the story just as it happened. “Suzanne” was, in every single passage, a play by play of his very real, and surprisingly platonic, friendship with a Montreal based dancer named Suzanne Verdal. Although the pair were never lovers, Suzanne became the most iconic and mysterious of all of Cohen’s muses. However, when unlocking the real life story of Suzanne, often the romance of mystery is far sweeter than the cruelty of reality.

There is plenty of information on the real life Suzanne Verdal out there, and the much told story of her friendship with Leonard Cohen seems to be retold accurately over multiple sources. But as to the fate of Suzanne, different writers seem to take different angles. Some try to maintain Cohen’s idealistic memory of her, portraying her as a woman who lived a modern Roma existence that has chosen to stay outside of conventional society. Others have shown Suzanne in a far more tragic narrative, as a woman who has somehow survived by a thin thread, living with crippling injury, homelessness, poverty and shattered dreams. Many prefer to just focus on the romance and try not to go any deeper than the Suzanne Leonard Cohen wrote about in 1965 and end the story right where Cohen left it at Suzanne’s “place near the river.” I can’t claim that I can present anything new about Suzanne Verdal which other writers before me haven’t, but perhaps by joining some of the different narratives together a complex portrait of a real life muse, filled with both romantic promise and tragic disappointment, and how she inspired the words that launched Leonard Cohen to international fame, may emerge.

Leonard Cohen first met Suzanne Verdal when he was a student at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec at the tail end of the 1950’s. As the Bohemian capital of Canada, Montreal clubs and coffee shops were filled with artists and beatniks looking for a new form of artistic expression. Closer to the Parisian experience than the scenes exploding in New York and San Francisco, Montreal’s art scene was full of an old world romanticism. With a tight community of artists forming, Cohen was a fixture on the scene, filling his notebooks full of words and observations, as well as playing in a Nashville inspired country group called The Buckskin Boys. Just where and when he first met Suzanne is unclear, but Suzanne has suggested it may have been while she was dancing at Le Moulin Le Vieux. Truth was, to Suzanne Leonard Cohen was just another guy in a sea of artists on the scene, and she had eyes for only one man – artist and sculpture Armand Vaillencourt. Already celebrated in Montreal at that time, Vaillencourt was somewhat older than the teenaged Suzanne, but the two became a noteworthy couple on the beatnik scene and were remembered for their energetic dancing at bohemian hot spots. According to Cohen in a later interview, “Everyone was in love with Suzanne, but nobody would try to seduce her because of Armand.”

Little biographical information on Suzanne seems to exist prior to this time, but she became well known in the Montreal scene not only for her pixieish beauty, but as a creative choreographer who pushed boundaries in her modernist approach to dance and for her elaborate futuristic costume designs. Vaillancourt and Suzanne eventually married and had a daughter together. Meanwhile, Leonard Cohen left Montreal in 1959 for Europe, eventually settling on the Greek island of Cyprus where he wrote the majority of his earliest celebrated works.

It was in 1965, when Leonard Cohen returned to Montreal to publish his second novel “Beautiful Losers” that the narrative that we know from the song took place. Upon his return, Cohen encountered Vaillencourt and inquired about Suzanne, only to learn that they had separated and that Suzanne was raising the couple’s daughter by herself at a small hovel near the Montreal harbor. Curious to see her again, Cohen sought Suzanne out and the two formed a friendship.

According to Suzanne in an interview with the BBC, her small ram shackle home had “crooked floors and a poetic view of the river.” What would come to be a continuous part of her narrative is that Suanne lived humbly, almost in poverty, and even at that time she shopped at thrift and secondhand shops and made her own clothes (“She’s wearing rags and feathers from Salvation Army counters”). Cohen would come to call, and Suzanne would put on tea, and serve Mandarin oranges, with bits of the peel put into the tea for flavor (“And she feeds you tea and oranges that come all the way from China.”) Suzanne would light a candle, which she affectionally called “Anastasia” believing it called on the “spirit of creativity” and the two would first sit in silence, before entering long conversations about art and philosophy and life.

Often Suzanne and Cohen would walk down to the St. Lawrence River and wander along the harbor (“Now, Suzanne takes your hand, and she leads you to the river.”) One of the local landmarks not far from Suzanne’s home was an old cathedral called the Notre Dame de Bons Secours Chapel. For centuries the church was, and remains to be, a place where sailors from all over the world have gone to pray for safe voyages on their journeys across the ocean. One of the most prominant features of the chapel is a statue of the Virgin Mary, which was mounted on top of the church overlooking the Montreal harbour in 1848, which Cohen pays homage to in the third verse (“And the sun pours down like honey on our Lady of the harbor.”)

Although Cohen and Suzanne would have intense conversations, and obviously had a connection during their visits, according to both of them, the relationship never turned into a sexual one. Suzanne has said that at the time she was still grieving the failure of her relationship with Vaillencourt, and while Cohen obviously saw Suzanne as a muse and was drawn to her for repeat visits, he didn’t want to damage the sacrament of their cerebral connection (“And you want to travel with her, and you want to travel blind/And then you know that she will trust you/For you’ve touched her perfect body with your mind.“)

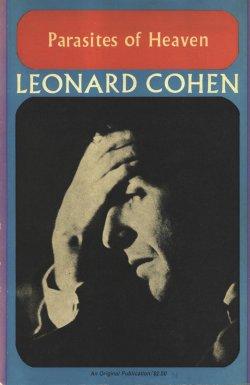

Inspired by his quiet visits with Suzanne and their walks along the river, Cohen wrote what is possibly his most famous poem, “Suzanne Takes You Down,” which was first published in his 1966 collection of poetry titled “Parasites of Heaven.” Surprisingly, Cohen never told Suzanne about the poem prior to it being published, which makes me believe that their intimate friendship was most likely brief. It wasn’t until Cohen had left Montreal that Suzanne learnt about the poem when a mutual friend of the two, filmmaker Derek May, told her about it.

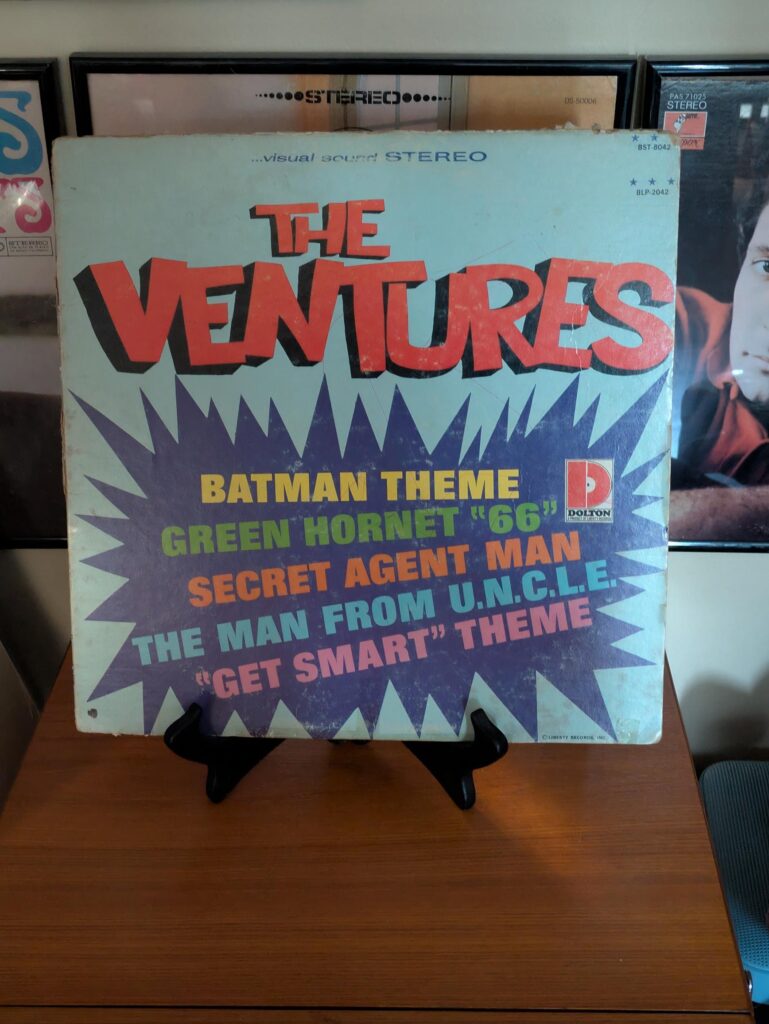

1966 proved to be a pivotal year in Cohen’s career when he shifted gears from poetry to music. Although he had achieved a certain notoriety in Canadian literary circles for his poetry, as well as for “Beautiful Losers” which proved to be a divisive novel amongst critics, just like struggling artists today, Cohen found it difficult to live as a writer. Poetry and experimental writing weren’t going to pay his bills or buy his groceries. Looking over his poetry, he began to wonder if he could transform his more lyrical poems into songs. It would be a challenge, because Cohen’s lyrics were not the kind that would find popularity on pop radio, and they were often even too wordy and moody than the most experemental records. But, having tinkered with the guitar since his days at McGill, Cohen started to play around with his words and put them to melodies. “Suzanne” seems to have been the earliest of his songs to move from the page to music, with the earliest recorded version of it being a live performance by a Canadian folk group called The Stormy Clovers. I have looked for information on The Stormy Clovers, and although I started down a few rabbit holes in which I felt I was getting close to finding information on them, I’ve failed to find enough to reliably write about the group. Some sources say they were a Toronto based group, while others claim they were from Montreal. However, it does seem that the members of the group did know Leonard Cohen on a social level. I’d love to learn more about The Stormy Clovers, and if anybody has more information please reach out.

Apparently, as a result of living on Cyprus at the beginning of the 1960’s, Cohen was completly out of touch when it came to the popular music trends in North America, including the folk renneassance of the early 1960’s, and his initial idea was to head to Nashville to write for country artists. Thankfully, via conversations with colleauges with far more knowledge of the contemporary music scene, Cohen skipped Nashville and, instead, went to New York City and implanted himself as a sort of outsider within Greenwich Village. Hanging out on the fringes of Warhol’s factory crowd, he became infatuated with Nico, and started going to Velvet Underground performances, where he became friendly with Lou Reed and John Cale (decades later, Lou Reed would induct Leonard Cohen into the Rock n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 2008, while John Cale recorded one of the first covers of “Hallelujah” in 1991, starting the juggernaut which it’d become). Like many artists at the time, Cohen got a room at the Chelsea Hotel, where he spent his nights taking acid and continuing his efforts to turn his poetry into music, but he was filled with insecurity over his endeavours. Although he made friends on the fringes of the art community in New York, Cohen still seemed to stand in the shadows, just outside of success.

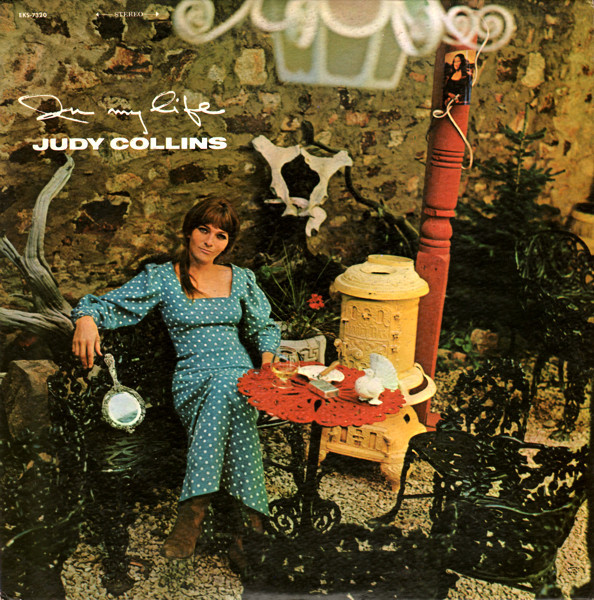

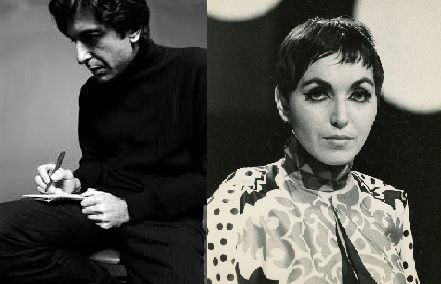

But Leonard Cohen’s fortune changed when he was introduced to folk singer Judy Collins by their mutual friend Mary Martin, who was a New York based childhood friend of Cohen’s from Montreal. Collins was working on her sixth album, “In My Life,” but was short on songs. Martin talked up Cohen to Judy, who was intrigued, and a meeting was arranged between the two. Leonard Cohen showed up at Judy’s apartment and, according to her in an interview with the CBC, he introduced himself by saying “”I can’t sing, and I can’t play the guitar. I don’t know if this is a song.” However, he swallowed the nervous lump in his throat, and the first song he played for her was “Suzanne.” Although nervous and uncomfortable, the intensity and sensitivity of the song had a giant impact on Judy, who instantly saw the magic in his words and music. By the end of their meeting together, Judy Collins agreed to record “Suzanne,” as well as another Cohen composition, “Dress Rehearsal Rag.”

“In My Life” was released in November 1966 and was well received by audiences and critics, and despite having no singles released it managed to go to the #46 spot on Billboards albums sales charts and got its Gold certification. But the outstanding track on “In My Life” was without a doubt “Suzanne,” which became an instant part of Judy Collin’s catalogue. Judy’s fans fell in love the song while music insiders became very curious about who this unknown songwriter from Montreal was, and what more he might have to offer. Although Cohen was pleased with the success of “Suzanne” under Judy Collins, Judy felt that he had far more to offer, and much to his resistance, she began to push him to perform with her in front of an audience. Although he wasn’t at all a conventional performer, Judy Collins saw the dark beauty in his personal delivery, and the powerful fragility in his flawed vocals. But by that point in music, artists such as Janis Joplin and Bob Dylan had both proven that you didn’t need to be conventional to find a fanbase. Whatever it was that Leonard Cohen had, Judy saw it and she believed in it, even if he did not.

In July 1967 Judy was to appear at a benefit concert for SANE at Philadelphia’s Town Hall. Headlining the show was The Doors, who packed in a huge crowd. But the crowd waiting for Jim Morrison to arrive were about to witness an unexpected historical debut. During Judy’s set, she stopped to talk about “Suzanne,” but instead of performing it she asked Leonard Cohen to come to the stage. With his legs shaking, Cohen took center stage with his guitar in his hands, and as a hushed crowd watched in wonder, he began to sing “Suzanne” in front of an audience for the first time. However, after only a few lines he suddenly stopped and said to the audience “I’m sorry. I can’t go on” and he walked off the stage. With tears in his eyes, the clearly shaken Cohen went to Judy backstage and said to her “I can’t do this.” Meanwhile, the audience out front began to go nuts, yelling for him to come back and pleading for more. “I can’t go back out there,” he reportedly said to Judy. “But you will,” Judy replied. Gaining his composure, Cohen straightened up his shoulders, and Judy pushed him back out in front of the audience. Cohen began his song again, and this time he made it through to the end. The audience went crazy for him, and Cohen’s career as a musical performer had begun.

Over the next number of years “Suzanne” became a popular standard recorded by a wide range of musicians, including Noel Harrison, Neil Diamond, Nina Simone, Francois Hardy, Esther Ofarim and Roberta Flack. But the most important recording of “Suzanne” was Leonard Cohen’s own now iconic version, from his 1968 debut album “Songs of Leonard Cohen,” The first single was, of course, “Suzanne,” backed with “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.” However, the irony of “Suzanne” is that while it became a staple of sorts throughout the music industry, the song has never once been a Billboard hit for any artist ever. Cohen gained instant fame for it, and it became the gold standard for the majority of his career, but although its continuing popularity, it has never once climbed the charts.

But despite this, “The Songs of Leonard Cohen” found its own audience amongst intellectuals and musical hipsters. The poetry, intensity and old-world aesthetic of Leonard Cohen seduced the souls of listeners across the world, and the album sold well through North America, but particularly well in Denmark and England. Packed with songs that would become revered as some of Cohen’s greatest, including “So Logn Marianne,” “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye,” and “Sisters of Mercy,” the album solidly put Leonard Cohen on the map as a gifted song writer, and a cult favorite. He’d have to wait a few more decades for superstardom, but Leonard Cohen had arrived.

But what of Suzanne Verdal? What happened to the muse that inspired the song that launched Leonard Cohen, and did they ever cross paths again?

In various interviews with both Suzanne and Cohen, at least three future encounters between the two have been documented, but the timeline of when, or even if, they happened is a bit dodgy. The encounter than seems to be the most verifiable, as both Cohen and Suzanne have told of it, happened backstage at one of Cohen’s performances held in Minneapolis sometimes in the 1980’s. Seeing Suzanne amongst the people gathered offstage, Cohen crossed over to her and kissed her respectfully on the cheek and said to her “Oh Suzanne, you gave me a beautiful song.”

A second story, which I can only find one account for in the interview Suzanne did with the BBC, happened in Montreal sometime during Cohen’s rise to fame, possibly the 1970’s. According to Suzanne she encountered Cohen in a hotel lobby when he was visiting Montreal, and that he, for the first and only time, did proposition her to meet him later in his room, but she declined. In recollecting the possible proposition, Suzanne reflected “I forget that Leonard is more than just an amazing poet and philosopher. He is also a human being who happens to be a man.”

But the third, and final, encounter between them is heartbreaking and one that Suzanne has told many times over many sources. At an unnamed event she was performing at in the 1990’s, Suzanne saw Cohen and danced up to him and did a curtsy, but he did not react. It was as if he didn;t recognize her, and he did not speak to her afterwards. Disheartened by his reaction, Suzanne said that his indifference hurt her and has bothered her greatly over the years. If Cohen had ever heard this story, he never commented on it in his lifetime.

While Suzanne has given a number of interviews over the years, the most revealing article on her life after the success of Leonard Cohen’s song comes from a 2022 article by writer Lacey Warner, who tracked Suzanne to California and had a strange and revealing encounter where she successfully got Suzanne to open up about her life. Although written with compassion and empathy, Warner also wrote with honesty, revealing a portrait of a woman who has lived so long on the fringes of conventional society that her physical, emotional and mental health has suffered for it. Although I will outline some of the more important take aways from the article, I encourage anyone interested in Suzanne Verdal’s story to read Warner’s interview here, as it is a well crafted profile and a briallint piece of journalsim.

In Warner’s interview, Suzanne reveals that in the years after Cohen’s narrative, she continued to work as a choreographer and eventually opened her own successful dance studio. Well regarded for her creativity, Suzanne came to believe that other professionals who discouraged her ideas, went on to steal them for greater success and profit. This seems to be an ongoing theme in the interview, with Suzanne resentfully watching other artists and performers that were in her orbit find success, while she continued to struggle. As a result, a sort of paranoia over ownership, and a desire for owed composition, seems to consume her thoughts.

Suzanne eventually branched out to having a successful massage therapy career, but in 1992 she made a very bold decision to shut down her operations in Montreal and try to start a new career in Los Angeles as a cheographer for music videos. This proved to be a risky, and in all honesty unrealistic, decision. At this point Suzanne was in her 50’s, and Hollywood is a young person’s game. Historically, in only rare occasions has anybody made it in the Hollywood system if they hadn’t already become a part of it in their youth. But, having built a sort of shack on the back of a truck with the aide of a son she had in a later relationship, Suzanne drove from Montreal to Hollywood, sleeping in camping grounds and parking lots along the way. Warner was able to observe this modern caravan which she describes as being “a kind of wooden house that sits atop the flatbed, complete with windows and shingles, like a giant birdhouse on wheels.”

Once in Hollywood, Suzanne got an apartment with a man and entered a relationship with him. Although it sounds like it was a relationship of convenience, Suzanne says it quickly became an abusive one.

This led to an accident which would go on to affect the rest of Suzanne’s life. When climbing a ladder on her truck to get to the shack, the contraption broke and Suzanne fell to the concrete ground, smashing her body in a crippling manner that not only ended her career as a dancer but continues to cause her crippling pain today. She broke both of her wrists, as well as a vertebra in her back, which would go on to affect her organs. According to Suzanne, she believed the ladder was safe as the man she had been living with had claimed to have fixed it and she continues to blame him for the accident. Shortly thereafter, the relationship ended, and Suzanne found herself back in her truck with no home, no job, no money and no way to pay her medical bills. It does not seem that Suzanne has managed to bounce back since then.

The current narrative about Suzanne sees her as being homeless and living with the stigma that goes along with that. Although Warner did report that Suzanne lived in a one-bedroom hovel which she pays rent for in her interview, one of the more distressing narratives in the interview is Suzanne’s attempt to extort money from Warner out of sheer desperation. Having myself experienced people who have lived on the edges of fame before falling on hard times, I recognized this sort of behaviour from interview subjects myself, and I could easily relate to the difficulty which Warner had when experiencing this side of Suzanne. Warner also would become victim to Suzanne’s paranoia and emotional instability in the aftermath of the interview, which she chronicles with sympathy and transparency. However, in the end, her article paints a bleak portrait of a one-time muse with all the myth and magic stripped from her.

The most current account of Suzanne’s status does not put a shiny coda to Warner’s experience but seems to build on the narrative. In April 2024 a GoFundMe campaign was started to help Suzanne financially. In a letter supposedly written by Suzanne, it claims that the home that she lives in, presumably the one on the back of her truck, had caught on fire and was now unrepairable. Continuing the narrative of her homelessness, the letter continues to say that the campaign was started by her son in law, Chris Berggren, to aid her with rebuilding her life and helping her gain shelter. I tried to find more details on this, as well as find information on Berggren, to verify the details of the claims in the campaign but came up with very little. To date a little more than 7K has been raised of the 100K which the campaign has hoped to raise. Whatever the campaign is valid or not, Suzanne, who is now in her 80’s, is clearly a woman in financial crisis and anyone caring to help her can visit the GoFundMe Campaign for more information at https://www.gofundme.com/f/help-suzanne-verdal-get-a-home. If anyone representing Suznne Verdal or this GoFundMe campaign could provide more details on the validity of the campaign and its progress, please reach out so we can support it more actively.

In searching for the real Suzanne Verdal, there is a romantic version chronicled by Leonard Cohen in 1965, and a tragic one as revealed by Lacey Warner in 2022. But no matter what the reality, in Suzanne Verdal, Leonard Cohen met a powerful muse which would help launch his music career and ultimately change his life. A woman of great presence and beauty that emotionally and intellectually stimulated one of culture’s greatest bohemian icons, Cohen created a mythology around her which seduced the imagination of people worldwide. But, as the stories of the muses that inspire society’s most celebrated artists often reveal, Suzanne’s real life journey proves again that often truth isn’t as beautiful as the fantasy that is weaved by poets and singers. But no matter where she is now, to the public Leonard Cohen has frozen Suzanne forever in time at her place by the river. Oh Suzanne, you really did give us a beautiful song!