It’s one of the most unsettling recordings ever made. Four young women, trying to unsuccessfully hold back their giggles, harmonize their girlish sing song voices to a philosophical riddle in the form of a nursery rhyme. If you listen close, you can hear the sounds of a cooing baby, and the gentle hum of a man who seems to instruct them:

For always is all is forever

‘Cause one is one is one

Look inside of yourself for your father

All is none, all is none, none is one.

t’s time to call time from behind you

The illusion has been just a dream

Valley of Death and I’ll find you

Now is when on a sunshine beam.

So bring only your perfection

For there love will surely be

No cold, pain, fear, or hunger

You can see, you can see, you can see.

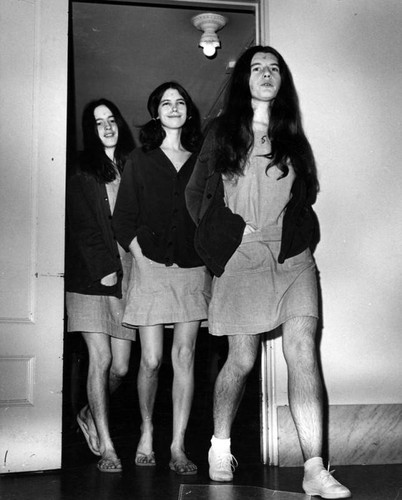

It may sound like girls at play in a school yard, or the poetry of Lewis Carroll or A. A. Milne, but this joyful medley is the sound of perverse indoctrination and sadistic evil. The song, titled “I’ll Never Say Always to Never,” was being sung by Catherine Shane, Sandra “Blue” Goode, Nancy “Gypsy” Pitman and Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme and the man leading the quartet was the song’s composer, Charles Manson.

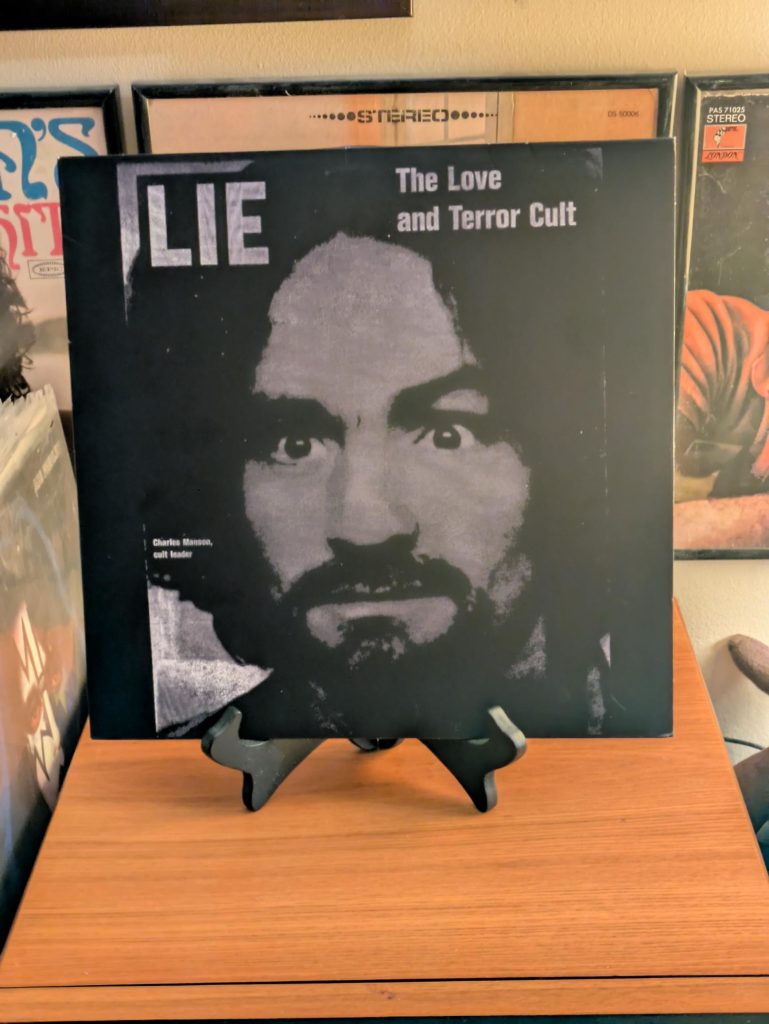

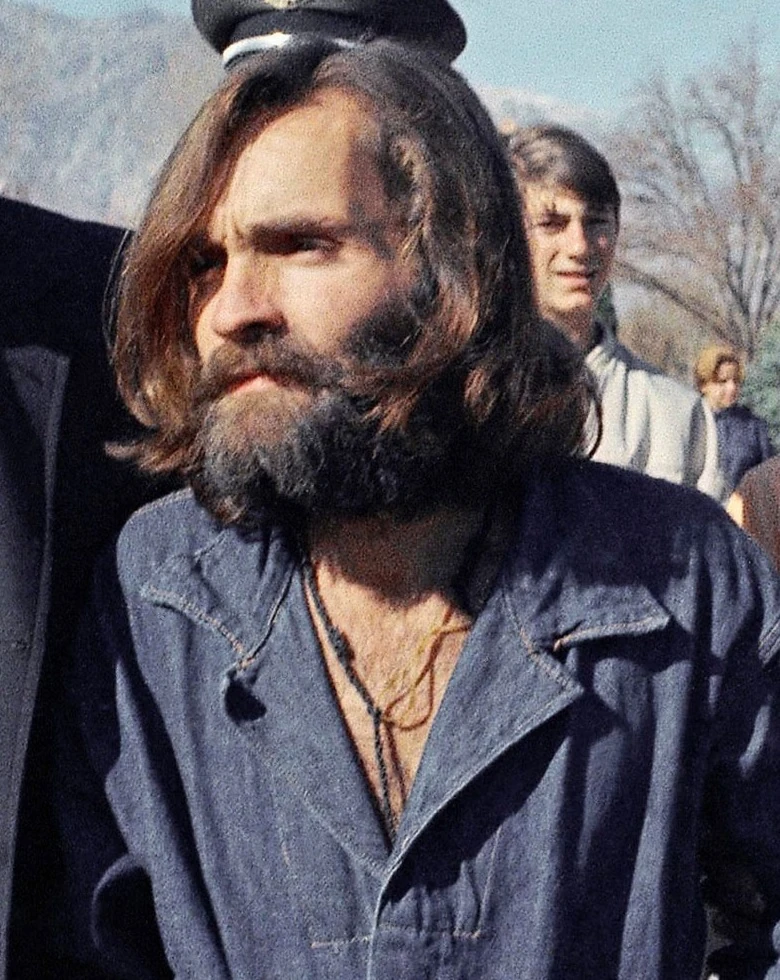

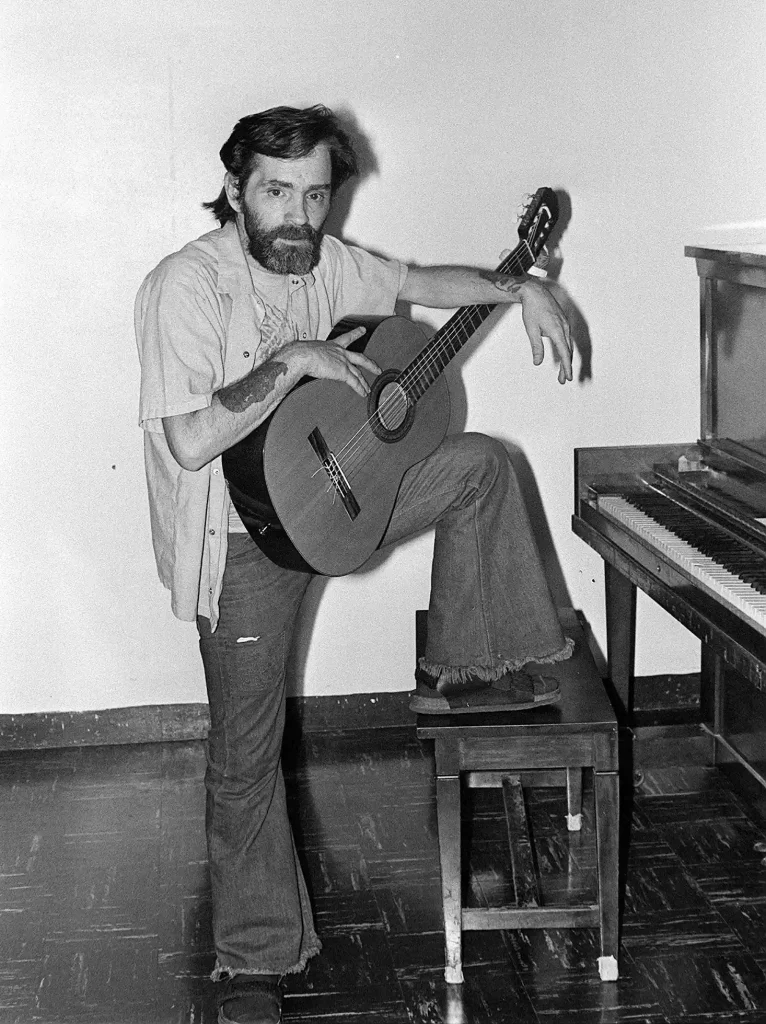

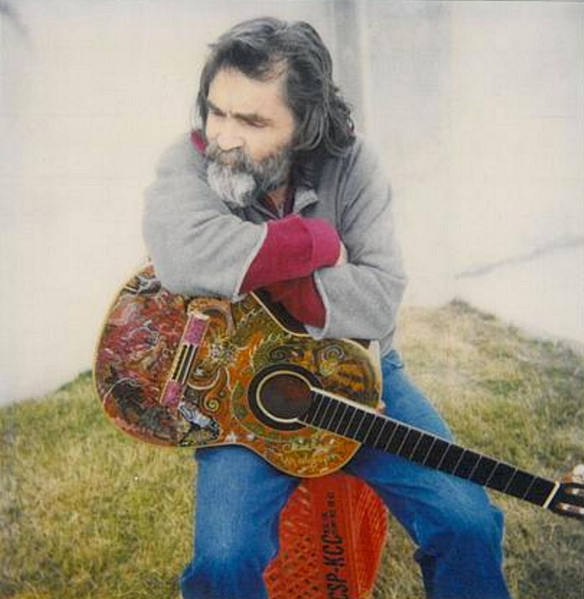

One of the most notorious villains of the 20th Century, Charles Manson has been called many things – career criminal, cult leader, killer, guru, leader, philosopher and father figure. But what seems to go overlooked is the one thing we know for certain Charles Manson was – a failed musician. His story has been told a million times in hundreds of different ways. We know about his family, his victims and the impact that his crimes had on 20th Century society. But still today his music goes unheard and dismissed, despite everything going back to the music – the message, the motive and the murders. Since 1970 Charles Manson’s music has been available for the public via “Lie: The Love and Terror Cult.” Cobbled together by a serries of recordings Manson and his “Family” made between 1967 and 1968, “Lie” is an interesting look into the mind, musing and melodies of a madman, which is easier to access today than ever before.

When I was growing up, in a time when the internet was still young, Charles Manson recordings were a thing of legend. You might have heard that they existed, but getting your hands on them was another story. But once in a while someone would come along who’d have a bootleg of “Lie,” and you’d find out that the Manson recordings were a real thing. I was in high school the first time I heard a recording of Charles Manson singing “Look at Your Game Girl” and I remember that, to my amazement, it wasn’t at all what I expected. By the 1990’s, the only Charles Manson we ever saw was his frantic ramblings on tabloid programs such as “A Current Affair” and “Geraldo.” But “Look At Your Game Girl” didn’t sound like that. It sounded more like a Donavan song, and its message, of re-examining your life in the face of despair or dissatisfaction, seemed like solid advice.

Although the basic story of Charles Manson and The Family is now infamous, the story of “Lie,” and how it came to be, reads like an alternative timeline in the often-repeated narrative, involving characters less talked about, primarily a guy named Phil Kaufman.

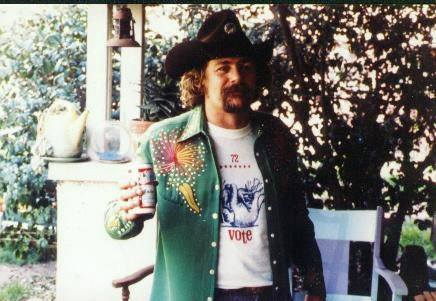

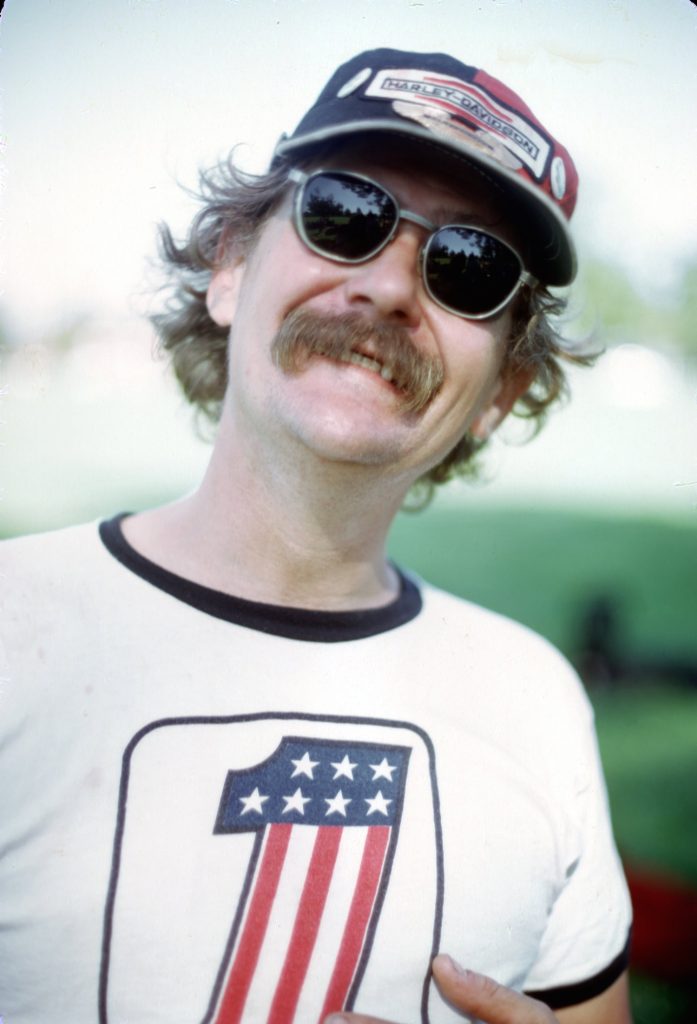

Show business was in Phil Kafuman’s blood before he was born. The grandson of a vaudevillian, and the son of a big band musician, Kaufman arrived in Los Angeles after a stint in the Air Force, which included four years in Korea. But beyond getting extra work in films such as “Spartacus” and “Pork Chop Hill,” Kaufman wasn’t very successful in regard to generating any interest from casting directors or agents. But, his acting career would be put on permanent hiatus anyhow when he was caught trying to sneak marijuana into Mexico, which landed him in Terminal Island Prison.

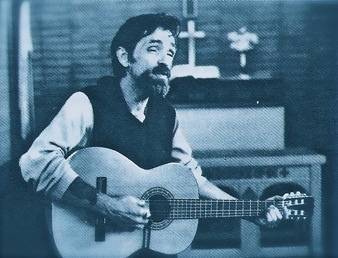

Soon after entering the pen, Kaufman noticed a young man playing a guitar in the prison yard. Interested in music, Kaufman went and joined the other inmates who stood around listening. However, the performance as interrupted when a passing guard taunted the musician by saying “You’re never going to get out of here.” The musician stopped playing his guitar, looked up at the guard and slyly responded “Get out of where?” This was Phi Kaufman’s introduction to Charles Manson.

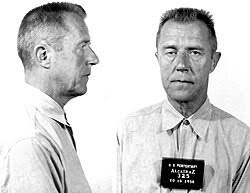

Incarcerated at Terminal Island in 1960 for a plethora of charges, Manson had already spent the majority of his life behind bars. It was during this stay that Manson first showed an interest in music, and approached one of the prison’s most notorious inmates, Alvin “Creepy” Karpis, to teach him to play guitar. A member of the legendary prohibition era Ma Barker Gang, Creepy had his doubts about Manson at first, but upon feeling sympathy for him, Creepy reluctantly taught Manson to play. Charlie caught on quickly and soon was composing his own songs.

Kaufman and Manson eventually formed a friendship primarily around their mutual interest in music and the entertainment industry. Kaufman found Manson to be good company, and saw a value in his songs, and encouraged him to pursue music when his parole came up. Going in front of the parole board in March 1967, Manson stated that he planned to get a career in music to sustain him on the outside, and he was granted his freedom. Prior to leaving the pen, Manson had asked Creepy if he could hook him up with some music contacts in Vegas, but the former gangster relented, feeling uneasy about giving Charlie any aid outside the pen. However, Kaufman advised Manson to take some time to pull himself together on the outside, and once he had some polished music, look up his friend Gary Stromberg who worked for Universal Pictures.

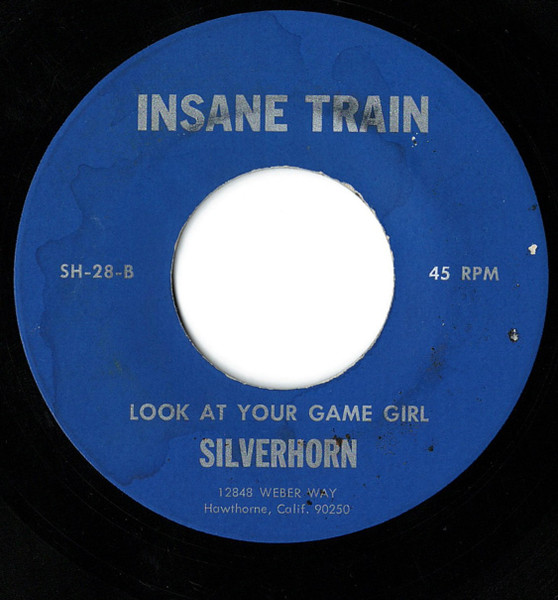

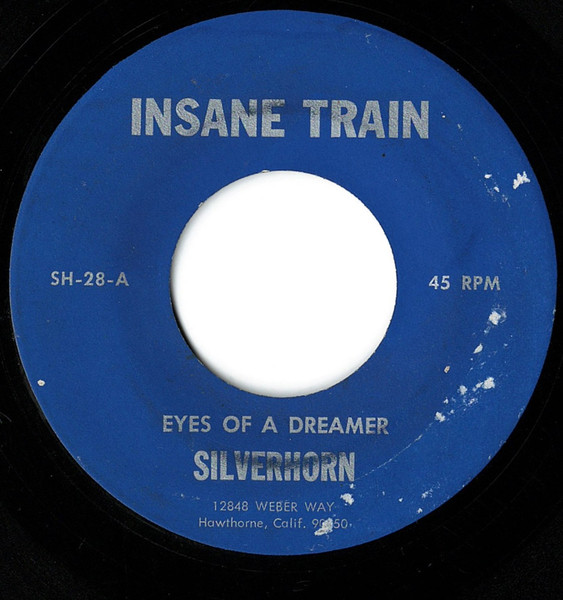

In the months following his parole, Manson took off to San Francisco for Haight-Ashbury, where he began to attract the flourishing hippie scene with his acid drenched philosophy and his folk flavored music. But Manson soon grew weary of the Haight crowd, and soon he and his growing “Family” of followers were back in Los Angeles, and he gave a call to Gary Stromberg as Kaufman had suggested. Now Stromberg wasn’t a music guy, but the figure of a vagabond counterculture guru showing up in a bus with a guitar and group of followers interested him for other reasons. Stromberg was in the early stages of developing a film about the second coming of Christ where he comes back as a black man through the ranks of the flower people. Stromberg was eager to pick Manson’s brain for potential inspiration for his film, and in the process agreed to finance a demo recording via Uni Records. The result was a 45-rpm single with “Look at Your Game Girl” on the A side, and “Eyes of a Dreamer” on the B side. Instead of putting his own name on the album’s label, Manson chose the name Silverhorn. Only one copy of the 45 rpm was apparently made, which Manson kept with him.

Not long thereafter, Phil Kaufman was released from prison, and through Stromberg, reconnected with Manson on the outside. Living with Manson and the family for a time, Kaufman liked the drugs, and he liked the sex, but eventually his attention went back on Manson’s music. Still believing in Manson’s ability to become a marketable musician, Kaufman arranged it with Stromberg to co-produce another round of demo recordings. On August 8, 1968, Manson, accompanied by his chorus of Manson girls, as well as his associates Bobby Beausoleil and “Clem” Grogan, who played electric and bass guitar, went into Gold Star Studios for a full day of recording. Gold Star Studios was the same studio that Phil Spector recorded his “wall of sound” hits, and Brian Wilson did his “Smile” sessions. Over several hours Manson and company cut a number of tracks including “Cease to Exist,” “Mechanical Man,” “Don’t Do Anything Illegal,” “Ego,” “Home is Where Your Happy,” “Sick City,” “Big Iron Door” and, of course, the Manson’s girl’s acapella melody “I’ll Never Say Never to Always.” The quality of these recordings were far inferior to that of the previously recorded songs from Uni Records, and while Manson managed to get through some of the numbers, others were noticeably interrupted or cut off. By the end of the day Manson and the Family had recorded another twelve songs ranging in quality. Although noticeably underproduced, Manson’s philosophical ballads and nihilistic songs of madness were successfully preserved on tape.

In the weeks that followed, Phil Kaufman moved out of the Manson compound. In later interviews Kaufman claimed that he and Manson never had a falling out, but that he saw through Manson’s façade and wasn’t buying the message he was laying down after awhile and that he felt it was time to bow out. Believing to still be on good terms with The Family, Kaufman stumbled into an opportunity that would change the trajectory of his life when he got a job as a driver for Mick Jagger who was in Los Angeles with The Rolling Stones recording their 1968 album “Beggar’s Banquet.” With his big personality and street-smart sensibility, Kaufman endeared himself to the Stones starting a long association with them, which became the gateway to a long and illustrious career in tour management.

Meanwhile, Gary Stromberg brought the Manson demos to his colleague Russ Regan, who was the head of Uni Records. Regan listened to the rough recordings and said “Just get rid of these. They’re terrible” and that was the end of the discussion. Stomberg intuitively did not scrap the recordings, but he let a disappointed Manson know that there was no more that he could do for him in regard to his recording career. Furthermore, with his film project about the second coming of Christ officially cancelled, Stromberg parted ways with Manson.

What happened next with Charles Manson and his followers has been told and retold countless times. Instead of going into great detail, I’ll give a superficial account of Manson’s movements after the Gold Star sessions for context, but there is a plethora of material in the forms of books, documentaries, movies, articles and podcasts for those who want more information. You’ll have little problem finding it.

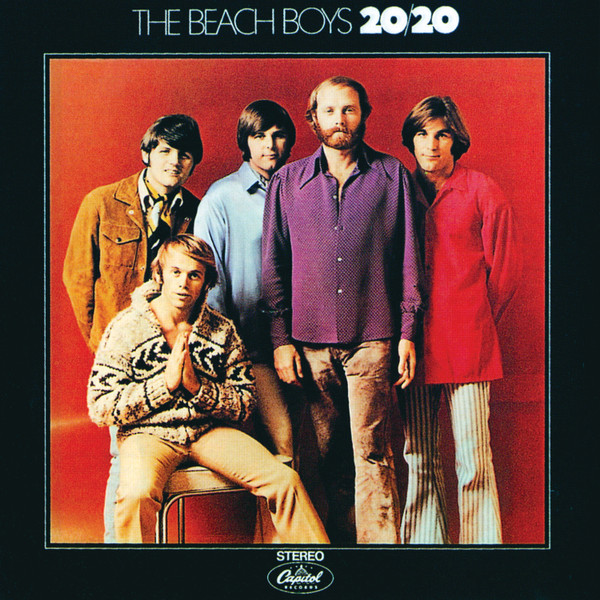

Weeks after the recording session, The Beach Boy’s drummer Dennis Wilson picked up a pair of Manson girls hitchhiking in Malibu. Bringing them back to his house, the girls told Wilson about Manson and his teachings. In less than 24 hours, Manson and the family had moved into Wilson’s house. Over the next six months, Wilson partied with the Manson Family while Manson tried to use Wilson’s influence in the music industry to launch his career. This would lead to the production of ten demo tracks being recorded by Dennis, assisted by his brother Carl, at Brian Wilson’s home studio, Those recordings have never been released and, if they still exist, are in the possession of the Wilson Family.

Dennis introduced Manson to producer Terry Melcher who was not only worked with The Beach Boys but helped launch The Byrds and Paul Revere and the Raiders to fame. Manson believed that Melcher was his best bet at launching a music career, but after a number of disastrous meetings and failed auditions, Melcher had an uneasy feeling about Manson and reportedly said to him “Charlie, there just isn’t anything I can do for you.” Melcher’s rejection of Charles Manson is believed by many to be the crushing blow that became the catalyst of things to come.

In the months that followed Manson’s mood and messages became even darker. As The Family purged dumpsters around Los Angeles, and a number of Manson’s associates mysteriously “disappeared,” Manson and his followers gained the attention of the LAPD but were deemed more of a nuisance than a menace. At this time Manson became obsessed with The Beatles newly released “White Album,” and believing The Beatles were sending messages directly to him, developed a concept he called “Helter Skelter.” Preaching about a race war which would have the black population rising up against the white race, Manson believed that if he could hide out in the desert, he’d be able to come out of hiding after the chaos and rule the black men as their leader.

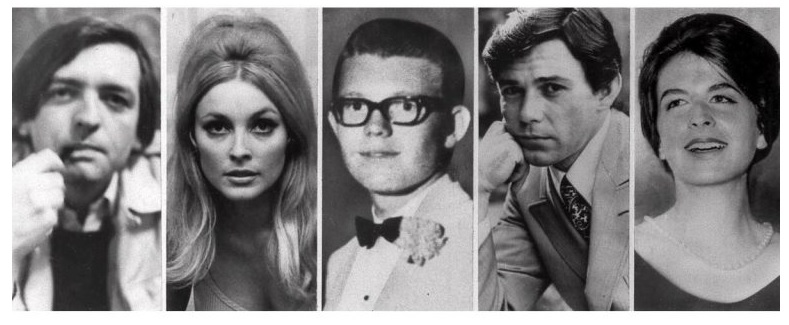

On April 9th, 1966, In an attempt to fast track “Helter Skelter,” Manson instructed four of his followers; Tex Watson, Patricia Kernwinkle, Linda Kasabian and Susan Aitkins to go to Terry Melcher’s house in the Hollywood Hills and slaughter everyone on the premise. In the early morning of April 9th, Watson, Krenwinkel and Atkins entered the property (Kasabian was left behind as a driver/look out) and murdered five people. However, Terry Melcher no longer lived at 10050 Cielo Drive. Having moved out months earlier, the house was now rented to director Roman Polanski and his wife, Sharon Tate. Tate, pregnant at the time, was murdered along her friends Jay Sebring, Abigail Folger and Wojciech Frykowski. Another victim, Steven Parent, was in the wrong place at the wrong time and was also killed.

The following night, while LA was still in shock, Manson drove Watson, Krenwinkel and Atkins, as well as a new accomplice, Leslie Van Houten, to the home of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. Seemingly picked at random, Manson stayed long enough to make sure the couple were detailed and then ordered his followers to kill the couple as he left the house.

Paralyzing Los Angeles in a state of fear, and seemingly no motives or reason for the killings, the LAPD increased operations while the Tate-LaBianca murders made front page news worldwide. Within four months Manson and his conspirators would be arrested an incarcerated. Manson was apprehended in December 1969, marking the end of the free loving 1960’s.

And this is when Phil Kaufman returns to the narrative.

When Manson and company were arrested, Kaufman had started working as a road manager and assistant to Gram Parsons. Parsons had split ways with The Byrds a year earlier and had formed his new group, The Flying Burrito Brothers. Meeting Parsons through an introduction from Keith Richards, Kaufman had become an important part in Parsons’ operation, as one of his closest friends and confidants.

Kaufman was initially shocked that Manson and his followers had committed the Tate-LaBianca murders, not believing that Manson had it in him to commit such an atrocious crime. He knew Manson was crazy and that he was a career criminal, but up until then he didn’t think Manson was a killer. But weeks after Manson’s arrest, Kaufman received a message via Squeaky Fromme and Sandra Goode that Charlie wanted to talk with him. Days later, Kaufman got a collect call from the state pen and Manson had one request – “Get my music out.” Manson believed that now that he had the attention of the public, people would finally want to hear his music and the profits from album sales would pay his legal fees.

Although he had his own successful gig in the music industry going, Kaufman saw a unique opportunity in front of him, and he contacted Gary Stromberg, who gave him the Manson recordings from the Gold Star Studio sessions. However, as far as Stromberg knew, the initial tapes for the earlier recording session featuring “Look At Your Game Girl” and “Eyes of a Dreamer” no longer existed. Retrieving Manson’s personal copy of the 45 rpm from Squeaky and Blue, Kaufman was able to duplicate the recording by playing back the record and recoding it directly on tape. Putting together a fourteen-track collection of what he had, Kaufman was able to cobble together Charles Manson’s first, and only, studio album. It was rough, but it was all Kaufman had to work with.

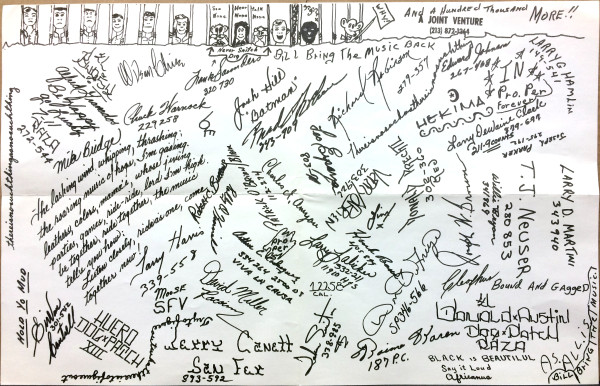

Kaufman spent the next few months trying to interest people in the record business to release the album, but nobody wanted to touch it. Thus Kaufman took a leap of faith and financed the album out of his own pocket. On his own label, which he called Awareness Records, Kaufman pressed two thousand copies of the album he titled “Lie: The Love and Terror Cult.” Charli’s photo from the cover of Life Magazine was reproduced on the front cover, and the album even came with a poster containing messages and scrawling’s from members of The Family and other Manson supporters.

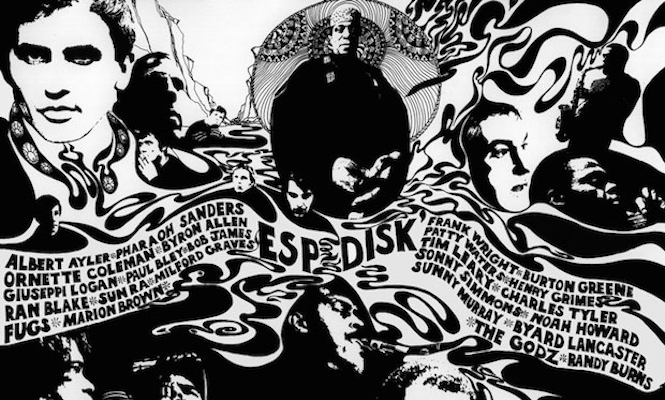

Not available in stores, “Lie” was advertised for order in underground newspapers and magazines. Meanwhile, members of The Family, who kept vigil daily in front of the Los Angeles courthouse daily, sold copies of “Lie” to curious spectators and tourists. In the end only about three hundred copies of the album were sold. In an attempt to regain the money, he put into the production of “Lie,” Kaufman signed the remaining copies for distribution to a New York based company called ESP-Disk. Whatever happened to those 1700 left over copies is anybody’s guess. However, if you are able to find an original copy of “Lie” today you are sitting on an album worth at least a thousand dollars of more, especially if you have the poster with it. Currently on Discogs only three original copies are for sale, all fetching for exuberant prices.

In the end Manson never received any money for the production and sale of his album. A California law prevented criminals from profiting on their crimes, and all funds raised by Kaufman for “Lie” was donated to a California based fund for the victims of violent crime. Decades later, as copies and reissues of “Lie” became available, the proceeds made from the sale of the album were apparently transferred to the remaining family members of Wojciech Frykowski.

Of course, Manson and his conspirators were tried and found guilty, becoming amongst the most celebrated criminals in American history. But despite the continuing interest in Manson and his crimes, demand and interest in “Lie” was non-existent throughout the 1970’s. But in the 1980’s bootleg versions of the album began to get quietly traded amongst collectors and audiophiles. Eventually an official version of “Lie” was released in 1993 on CD by a UK company called Grey Matter, and America would get an official CD releaser via ESP-DISK, who to this day continues to hold the right for the album, in 2006. Eventually an official rerelease of the vinyl was issued via ESP-Disk in 2017, and for nostalgia nerds, “Lie” even got its first 8-rack and reel to reel releases in 2022. Today “Lie” is more readily assessable than ever, available for streaming on Spotify and, of course, being available on YouTube.

But there are some additional curious facts about the recordings that connect “Lie” to the murders. While Charles Manson obviously chose the house on Cielo Drive because it was once the residence of Terry Melcher, it was initially believed that the LaBianca murder was completely random. However, further investigation showed that the LaBianca’s lived next door to a house in which Phil Kaufman had once lived, and that the Manson Family had once attended a party at. Why had Mason picked that particular house? Is it possible that Manson initially had hard feeling towards Kaufman in regard to not releasing his music faster, and that he had gone to the wrong house looking for revenge?

Upon his arrest, investigators reported that Manson had a list of people he wanted dead, including high profile celebrities such as Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton, Frank Sinatra and Natalie Wood. In 2017 Gary Stromberg found out that he too was on the list of people who Manson sought revenge on. Although his approach was apparently softer than Melcher, Stromberg had also dashed Manson’s musical ambitions, and he was lucky the authorities caught up to Manson before it cost him his life.

But the most bizarre detail is the date of the recording session at Gold Star Studios. The recordings were done on August 8th, 1968. Exactly one year later, August 8th, 1969, Manson ordered his followers to descend on Cielo Drive and spearhead “Helter Skelter.” Was this a coincidence? When it came to the madness of Charlie Manson, was anything ever a coincidence?

As I said, everything comes back to the music. The message, the motives, the murders.

So, the question remains. Is the material on “Lie” actually good? For decades people have been quick to dismiss Manson’s music. Critics and commentators have called it terrible, often criticizing Manson’s sloppy handling of the guitar and rough vocals. However, is the music actually terrible, or is the critics just uncomfortable that it exists? Are people too scared to admit that Charles Manson’s music just might have had some quality to it?

In reassessing Manson’s music, we need to keep in mind that the recordings are extremely unpolished demos. Manson is playing on an old guitar, possibly untuned and with old strings. He isn’t being accompanied by professional performers, and the recordings themselves are not properly mixed. Furthermore, Manson was said to be nervous, distracted, tired and frustrated. In some recordings, which end abruptly, you can clearly hear when Manson is fatigued.

But, in all honesty, some of Manson’s recordings are extremely good. The original two songs from the Uni sessions, “Look at Your Game Girl” and “Eyes of a Dreamer” are extremely well crafted and performed songs, and could both have been hit records if given the proper push. “Home is Where Your Happy” has a poppy bubble-gum quality to it, and “Mechanical Man,” as bizarre as it gets, goes into experimental territory which would be popularized later by Frank Zappa and The Velvet Underground. And of course there is “I’ll Never Say Never to Always,” which is Manson’s sweetest song and could have easily become a counterculture standard. Instead it became Manson’s most recognizable composition when it was heard being sung through the courthouse halls by Krenwinkel, Atkins and Van Houten.

Then there is “Cease to Exist,” which had such obvious promise that The Beach Boys stol….uh…..recorded it themselves for their 1969 album “20/20.” Retitling the song “Never Learn Not to Love,” Dennis claimed the song as his own after ending his association with The Family, believing that Manson stole and damaged so much of his property that the song was ample payment. Released prior to the Tate-LaBianca murders, The Beach Boys would attempt to divorce themselves from the song, but it would forever be a definitive reminder of their association with Charles Manson.

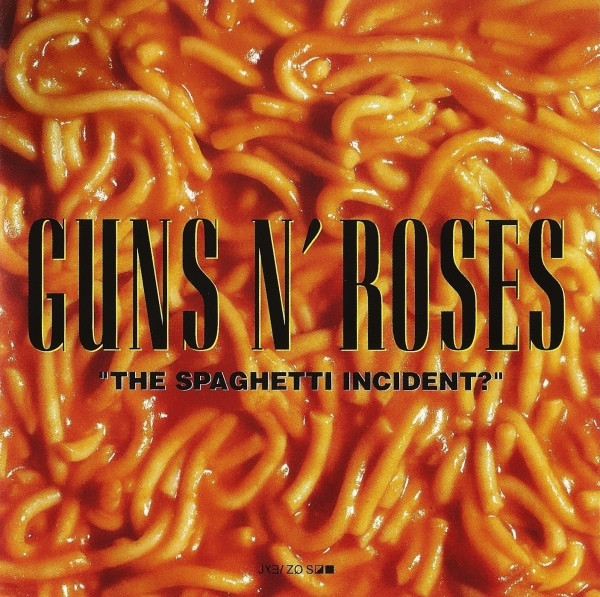

The Beach Boys weren’t the only major artists to record the music of Charles Manson. In the decades that followed, especially as copies of “Lie” became easier to acquire, a number of major artists revived Manson’s music. Possibly the most publicized time was when Guns n’ Roses made headlines when they included a cover of “Look at Your Game Girl” on their 1998 album “The Spaghetti Incident?” The inclusion of the song outraged parent and victim rights groups, who made a big noise about it, pushing for the track to be deleted from future pressings of the album. In the end it was left on as a “secret track,” and partial proceeds from sales of the album were donated to The Doris Tate Crime Victims Bureau. Meanwhile, The Lemonheads have recorded both “Home is Where Your Happy” and “Cease to Exist,” The Brian Jonestown Massacre covered “Arkansas;” Marilyn Manson covered “Sick City” and reworked “Mechanical Man” into his composition “My Monkey,” and actor Crispin Glover released a cover of “I’ll Never Say Never to Always.”

Of course there are also some pretty terrible songs on “Lie.” “Garbage Dump” is particularly painful to listen to. Obviously written as a comedic statement about class division, the song is Manson’s attempt at political satire, but it comes off as immature and amateurish. Songs like “Sick City,” “Don’t Do Anything Illegal” and “People Say I’m No Good” are interesting peeks into Manson’s criminal mind, but fail as actual compositions. Not everything on “Lie” is gold, but you know what? Not ever Beatles song was gold either. Especially those on “The White Album.”

But when I listen to the tracks on “Lie” I wonder what could have been if things had worked out differently for Charles Manson. What if Terry Melcher had agreed to record Manson’s music. What would these songs sound like with The Wrecking Crew backing him up? What would their quality be if the songs were properly mixed, Manson was given ample time to record each track, and if they had used brand new instruments. What would “I’ll Never Say Never to Always” be if The Ron Hicklin Singers had sung it? What was actually awful? Charles Manson, or his music? Some people have a difficult time separating the artist from the art. Others do not. In the end, the final say on the quality of Manson’s music sits with each individual listener.

Epilogue: His association with Charles Manson and masterminding the production of “Lie: The Love and Terror Cult,” is not the most notorious event of Phil Kaufman’s life. In the years to come Kaufman would become a well known music industry insider, acting as tour manager for a wide range of artists including The Rolling Stones, Etta James, Emmy Lou Harris, Joe Cocker and Frank Zappa (Zappa’s song “Why Does It Hurt When I Pee?,” from his 1979 album “Joe’s Garage,” was apparently inspired by one of Kauffman’s…uh….health problems). Bur Kaufman would make his ultimate footnote in music intimacy in 1973 when he and an associate stole the dead body of Gram Parsons, casket and all, from the Los Angeles International Airport, where it was on route for burial in New Orleans, and drove it out to Joshua Tree National Park and set it on fire…but that’s a different Vinyl Story for another time.