Just because you want to sing “Hallelujah,” doesn’t mean you should.

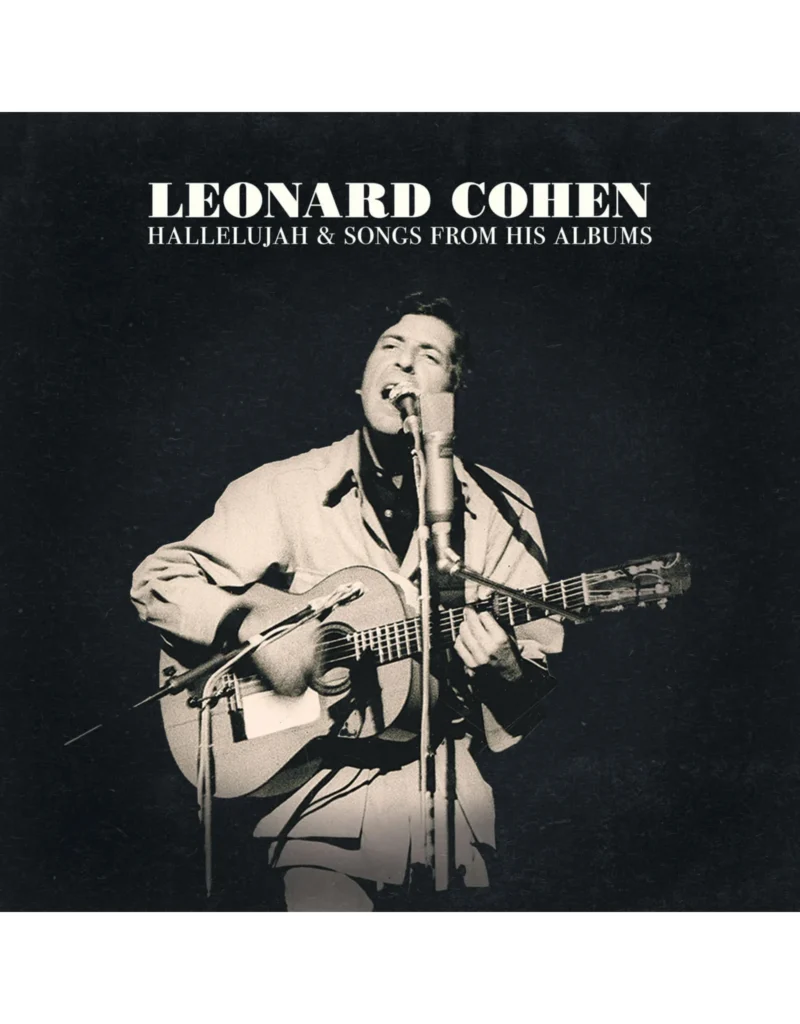

A few months back I was at an Indigo bookstore and flipping through a stack of overpriced 180-gram vinyl records that the popular chain store was selling. I always like to browse the vinyl section at these stores to see what they are stocking, but I have never bought anything there because the prices are usually exorbitant compared to that in an independent record shop. But, I suppose these sections are set up for the casual buyer who doesn’t have their thumb on the pulse of the vinyl market. Anyhow, as I was flipping through the stack I came across a Leonard Cohen compilation album I had never seen before titled “Leonard Cohen – Hallelujah and Songs from his Albums” (2022). My first knee jerk reaction to this title was complete disdain. I mean, I don’t want to be overly cynical, but I really felt this was one of the worst album titles I’d ever seen. I mean, it’d be like releasing a Led Zepplin album called “Stairway to Heaven and Other Songs They Sang,” or a Beatles compilation called “I Want to Hold Your Hand and Songs They Made Popular.” It seemed to me to be a title that was thought up in a corporate board room of people who didn’t have a love for Leonard Cohen’s musical legacy and just wanted to cash in on the massive worldwide phenomenon which is his composition “Hallelujah.” Let’s face it. That’s probably exactly what it was.and has b

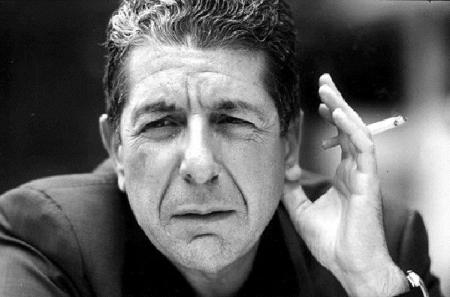

Despite Leonard Cohen being one of my cultural heroes and one of my very favorite songwriters and recording artists, I have a very combative relationship with “Hallelujah.” Possibly his most famous composition, the song is one of the most beloved songs of the modern era, and has transcended nations, cultures and genres as it gets rerecorded, and reinterpreted, again….and again…and again…….and again. And you know what? That’s my problem with it. According to multiple sources, overt he last thirty years nearly three hundred official covers of “Hallelujah” has been recorded, and it’s been used in a plethora of television shows and movies to the point that it’s become a parody of itself. Honestly, nothing will make me roll my eyes quicker than hearing the opening bars of “Hallelujah” and having to listen to another artist bleat it out dramatically. It’s one of my least favorite musical tropes..

But what often goes overlooked is that the popularity of “Hallelujah” is actually a modern phenomenon which grew completely organically without the aid of marketing or industry manipulation. In fact, when I first discovered Leonard Cohen in the early 1990’s, “Hallelujah” was little more than a deep cut from his undersold and under promoted 1984 album “Various Positions.” Nobody but the most diehard Leonard Cohen fan had heard of it, and the Leonard Cohen “standard” was “Suzanne.” But starting around the start of the millennium, “Hallelujah” snowballed into something that even Leonard Cohen himself could have never imagined, eclipsing all of his songs and poetry cherished for decades by his fans, to become the most recognizable of his compositions by the mass public. So while I don’t feel this particular song needs any more attention than it already gets, during my recent research on Cohen’s career I found the song’s history, and all the unexpected elements that made it a modern standard, to be too fascinating to ignore, so here I go listening to “Hallelujah” again.

My first exposure to “Hallelujah” came from listening to Leonard Cohen’s 1994 album “Cohen Live,” which I had purchased on cassette from Columbia House in one of those “Buy 14 albums for a penny” deals. Building off his mainstream success that he was receiving at the start of the 1990’s, “Cohen Live” was compiled of performances from his 1988 tour promoting “I’m Your Man,” and his 1993 tour for “The Future,” The third Cohen album I owned, the album opened up Cohen’s songbook even further for me from where “The Best of Leonard Cohen” had left off, bringing songs from his 1980’s period to my eardrums for the first time. Well, when I first heard “Hallelujah,” I will admit that I was gob smacked by its intensity and its beauty, and I remember thinking it really was a beautiful and powerful composition. I recognized it as being one of Cohen’s best and the majesty of “Hallelujah” was not lost on me in the least. But, in 1994 I hadn’t heard it a zillion times yet, and it hadn’t worn out its welcome in my personal soundscape.

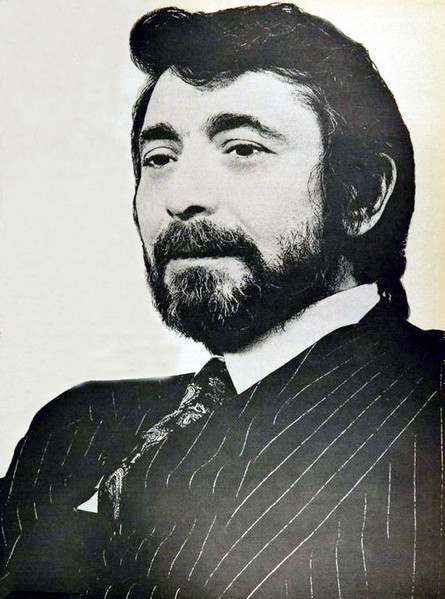

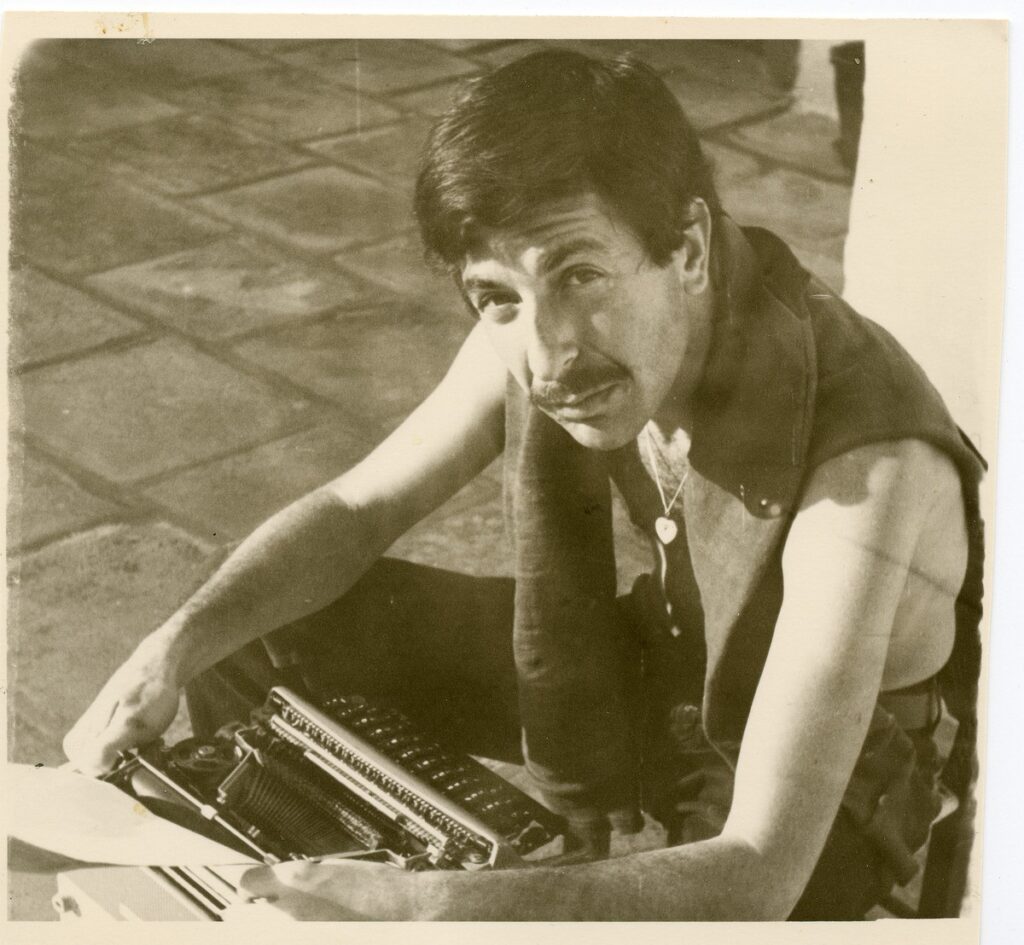

The popular lore is that Leonard Cohen had written more than eighty verses for “Hallelujah,” with his first draft being penned shortly after the completion of “Death of a Ladies Man,” his 1977 project with Phil Spector. After months in a toxic and dangerous work environment fueled by drugs and guns, Cohen found himself at a place in his life that he no longer recognized. With “Death of a Ladies Man“ being rejected by both critics and fans, Cohen’s relationship with Suzanne Elrod had come to an end, and he was expanding his own philosophical and spiritual beliefs by engaging in Zen Buddhism. Although he did record a forgettable, but well received album called “Recent Songs” in 1979, by the beginning of the 1980’s Cohen had pretty much stepped away from the recording studio in an effort to rediscover himself, and to focus on maintaining a relationship with his children, Adam and Lorca, in the wake of his separation. During a period where the state of music was going through massive changes, as the Disco era morphed into the MTV generation and pop artists started to overtake singer-songwriters in marketability, Leonard Cohen was pretty much absent from the industy, and not part of the popular musical culture.

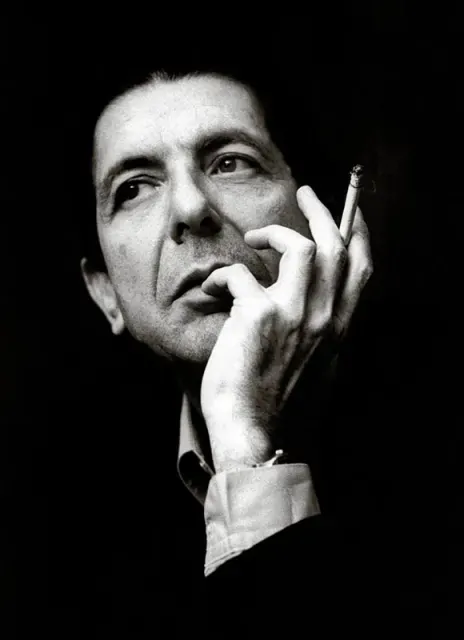

But while he may have been quiet, Cohen’s creativity continued to evolve. Two major developments would happen which would change the way Cohen made music at the beginning of the 80’s. The first was that his voice had noticeably dropped a number of octaves. Theorized to have been damaged due to cigarettes, liquor and age, Cohen’s voice took a moodier and darker tone, which nicely matched the potency of his lyrics. The other was that Cohen had purchased a small Casio keyboard and began to compose on it. Traditionally writing with his guitar, Cohen, who was never a brilliant keyboardist, fell in love with the new synthesized sounds, and although the old world feel of his previous songs got lost on the keyboards, it gave Cohen a new sound that was both modern and dystopian.

In 1983 Cohen had assembled a new collection of songs, and after a five year break from recording, he wanted to go back into the studio. However, for his new project he decided he wanted to go back to a time before Phil Spector came into his life and messed everything up and he contacted producer John Lissauer, who had produced Cohen’s last successful album “New Skin for the Old Ceremony” in 1974. Hired as Cohen’s musical director for a pair of tours after the release of the album, Cohen and Lissauer had planned to work together again on a project they were going to title “Songs for Rebecca,” but Cohen’s manager, Marty Machat, convinced him to work with Phil Spector instead, which killed the project before it even had life breathed into it. Although Lissauer had gone on to work with Al Jarreau and Barbra Streisand, when Cohen called him out of the blue after years of no communication and suggested they work together again, Lissauer was interested.

In June 1983 Cohen and Lissauer convened at Quadrasonic Studios in New York City to lay down the new tracks. Joining them for the project was a backing group called Slow Train, and a new background vocalist named Jennifer Warnes, who’d form a lifelong friendship with Cohen, and would eventually go on to have her own successful solo career. Over the summer Cohen and company recorded nine brand new tracks, some which would become important additions to his body of work. Particular stand outs included the album’s bookends, “Dance Me Until the End of Love’ and “If It Be Your Will,” as well as the emotionally potent “Coming Back to You.” But the standout track on the album was, without a doubt, “Hallelujah.”

The first track on side two, “Hallelujah” is the emotional center point of “Various Positions.” Filled with religious mythology and a choral backdrop, “Hallelujah” has been deciphered many different ways by many different people, which has opened the song up to so much interpretation that often the meaning goes unrealized or ignored by some of the people who choose to cover it. When reading through the lyrics of the version of the song on “Various Positions,” I feel it’s clear that “Hallelujah” is not a song about spirituality or salvation, although many religious groups have mistakenly appropriated it as a modern hymn. The lyrics are far too cynical, and there is an underlining feeling of lust and loss within them. There is a raw eroticisim in the retellisn of the stories of Samson and Delilah and King David and Bathsheba, and too much anguish and heartache to be a song about passion and love. I’m not going to be bold enough to take a stab at my own interpretation of “Hallelujah,” but Cohen was quoted as saying that the song came from “a desire to affirm my life, not in some formal religious way, but with enthusiasm, with emotion.” He would go on to say “There is a religious hallelujah, but there are also many other ones. When one looks at the world, there is only one thing to say and that’s hallelujah.” I’m not sure where he was going with that, but its clear to me that “Hallelujah,” although passionate and spiritual, is not a hymn nor prayer. It is something that goes much deeper where the human and the spiritual experience come together in ecstasy.

By the autumn of 1983 Lissauer and Cohen had completed recording the album and was left with an incredibly strong finished product. “Various Positions” is very much a transitional album, with moments of the old world influenced songs from Cohen’s early songs, as well as the darker dirges that would dominate his future albums. It also was the debut of his deeper vocal style, and his thrust away from acoustic ballads to more modern keyboards and synthesizers. “Various Positions” even saw Cohen indulging in his initial interest in being a country artist, with some surprisingly placed honky tonk vibes, most prominently on the politically charged “The Captain.” A new Leonard Cohen was evolving out of the ashes of the “Death of a Ladies Man” disaster, and “Variius Positions” was one of the best albums of his career. Team Cohen was pleased with the final product, but their enthusiasm was about to be completely dashed.

Sending it into Columbia Records, Leonard Cohen and Marty Machat were called to a meeting with CBS records president Walter Yetnikoff. One of the most powerful men in the record industry at the time, Yetnikoff told the men that he didn’t feel that “Various Positions” was marketable and that Columbia Records would not be releasing it. He then went on to issue the final insult by saying to Cohen, “Look Leonard, we know you’re great, but we don’t know if you’re any good.” This insult would burn a hole through Cohen’s heart, and he’d go on to quote it many times throughout his life, including during his acceptance speech when he received the Juno Award for Best Male Artist of 1993.

Now the knee jerk reaction is to say that Yetnikoff had no idea what he was talking about, but when looking at the artists that he was working with at the time he rejected Cohen, its fair to say Yatnikoff did have his thumb on the pulse of the music scene.. Yetnikoff helped deliver Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA,” Cindi Lauper’s “She’s So Unusual” and Billy Joel’s “An Innocent Man” to the world. It’s not that Yetnikoff didn’t know music, but he felt that Leonard Cohen, now at age 50, was not going to appeal to the kids who wanted their MTV and was questioning his relevancy on the mass audience. “Various Positions” seemed to be for too much of a niche audience that Yetnikoff didn’t have the patience to cultivate. So, to be fair, was he wrong about the marketability of the album? Possibly not. Did he understand the album? Doubtful. But, was he wrong about Leonard Cohen? Definitely.

The fallout of the rejection of “Various Positions” tremendously affected the team involved in making it. Looking for a scapegoat, Mickey Machat blamed John Lisseau for Columbia’s rejection of the album. In an explosive confrontation he reportedly said to Lisseau “You ruined Leonard Cohen’s career. This is the biggest disappointment of our lives,” before dramatically tearing up Lisseau’s contract and throwing it in the wastepaper basket. As a result of the destroyed contract, Lisseau apparently has never seen any residuals for the recording of “Various Positions” or for his work on “Hallelujah.”

It also put a dent in Cohen’s relationship with Machat, and although Machat still represented him, he basically decided that Cohen was prematurely finished and stopped getting him opportunities or engagements. He’d die in 1988 just as Cohen’s career started to finally enter the mainstream. Meanwhile, wallowing in his own depression, Cohen retreated to the tranquility of the Mt. Baldy Zen Center near Los Angeles, where he’d make his home on and off throughout the rest of his life, in an attempt to refocus his energy before deciding his next move.

“Various Positions” was eventually released quietly in December 1984 with no promotion or fanfare through an independent subsidary of Columbia called Passport Records, and only in Canada and Europe. It got its highest sales in Norway and Holland, who seemed to have embraced the album the most. Curiously, “Hallelujah” was released as a single in Canada and managed to become a minor hit on the Canadian RPM charts, although it peetered out at #17. But in the exciting flurry of the music scene in 1984, “Various Positions” floundered and went primarily unnoticed by record buyers and music fans alike.

So, if this was the final fate of “Various Positions,” how did “Hallelujah” come to be the most dominant song of Leonard Cohen’s career? Well, while Yetnikoff couldn’t see it’s potential, the song would become rejuvenated and eventually reborn through the voices of other artists that saw the power and beauty in Cohen’s words.

The earliest artist to brush off “Hallelujah” has been reported to be Bob Dylan, who began to perform it as part of his live performances around 1988. Ironically, he is possibly one of the only musicians who hasn’t actually done a studio recording of it, but live performances of Dylan’s version exists on the internet.

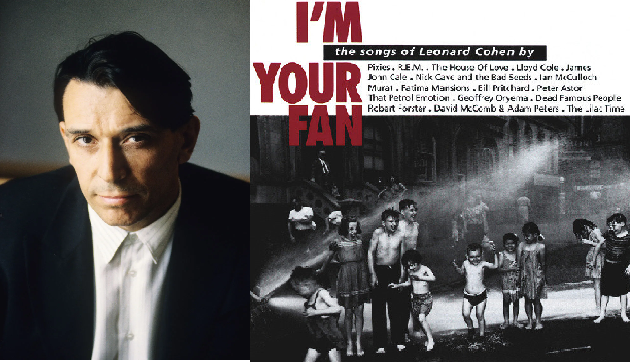

The true origins of the rebirth of “Hallelujah” came courtesy of British artist John Cale, who was an acquaintance of Leonard Cohen’s during his Velvet Underground days. Cale first heard “Hallelujah” when he caught Cohen perform in London,, Engl;and during his 1988 tour, and was taken aback by its majesty. A few years later Cale was invited to contribute a track to the compilation project “I’m Your Fan,” which had contemporary artists, such as The Pixies, R.E.M. and Nick Cave covering classic Cohen songs. Remembering “Hallelujah,” Cale reached out to Cohen and asked him if he’d fax him the lyrics for the song. What he got back was a fifteen page document with all eighty of Cohen’s original verses. Overwhelmed by the amount of material recieved, Cale went to work cherry picking what he felt were the “cheekiest” verses, and compiled his own interpretation of the song, which would prove to be different from the one that Cohen released on “Various Positions.” This would change the way that “Hallelujah” would forever be heard, as the reassembled version John Cale cobbled togther has become the lyrics that’d be covered and recognized by the masses in the decadees to come. Released in September 1991, at a crucial moment in time when Cohen’s music was reentering the musical landscape via his comeback album “I’m Your Man,” as well as his music being prominently featured in the hit film “Pump Up the Volume,” “I’m Your Fan” became an indie hit, and exposed a new type of audience to Cohen’s words and music. Although it still remains to be a strong album and well worth revisiting in its entirity, the standout track on the album was defintiley Cale’s version of “Hallelujah” which started to get played on university radio stations and be swapped by music hipsters.

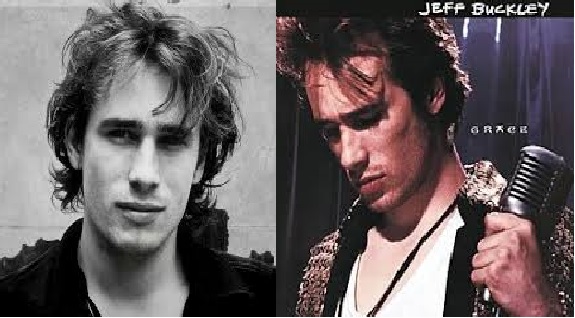

One aspiring musician who heard Cale’s version of “Hallelujah” was singer/songwriter Jeff Buckley. Son of folk musician Tim Buckley, Jeff began playing Cale’s version of “Hallelujah” as part of his sets, and eventually recorded it on his 1994 debut album, “Grace,” where it became a favorite by his small but loyal fanbase. But Buckley didn’t live to see his music hit the mainstream. When he tragically drowned in 1997, due to fan campaigns his album continued to rise in sales and he became a celebrated cult figure, giving Buckley more fame in death than he had in life. “Hallelujah” became an anthem for Buckley’s fanbase who mourned the death of a singer they barely got to know and became his most celebrated recording.

Jeff Buckly’s version of “Hallelujah” would eventually hit the UK Billboard charts in 2008, rising to the #2 position, following the release of a version by “X-Factor” contestant Alexandra Burke, whose version of it went to the number one position on the chart, making her the first artist ever to put “Hallelujah” on any Billboard chart. This was one of the few times in Billboard history that the top two positions were held by the same song being covered by two different artists. In a similar situation, Buckley’s version would hit the top of Billboard’s Digital Downloads chart after “Hallelujah” was performed on an episode of “American Idol” by singer Jason Castro. “Hallelujah” would not enter the American Billboard charts properly until 2010 when it was covered by Justin Timberlake and Matt Morris, where it went to #13. Ironically, it’d take Leonard Cohen to die before his version climbed up the Billboard charts, which it did for the very first time in 2016, thirty two years after it was released. A week after his death, it peaked at #59. This is the only time, to date, that Leonard Cohen ever had a song on the Amereican Billboard Top 100.

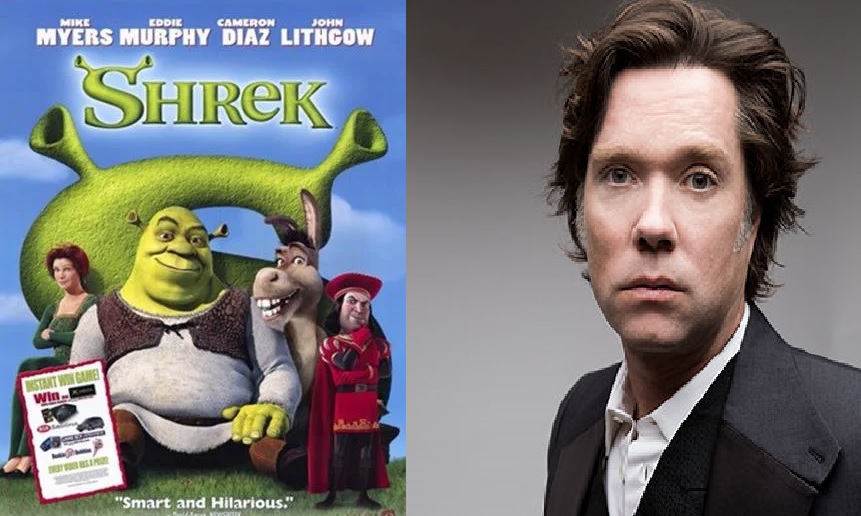

But tbe most monumental use of “Hallelujah” which possibly impacted its popularity on mass culture the greatest, was when the John Cale version was used during a pivotal scene in the 2001 film “Shrek.” One of the most successful animated films of the current century, “Shrek” brought “Hallelujah” to a much broader audience than ever before, endearing it to listeners of all demographics and ages for the very first time. For some unknown reason, when the soundtrack album to “Shrek” was released, the John Cale version was replaced by a different rendition of the song performed by Canadian artist Rufus Wainwright. Ironically, Rufus Wainwright would eventually become a part of the Cohen family when he fathered Cohen’s granddaughter Viva.

So while it was ignored in the 80’s, and was little more than a deep cut in the 90’s, by the dawn of the millennium “Hallelujah” was a monster of a song that suddenly started being used in more and more television programs and film soundtracks, getting covers by a plethora of artists ranging from Andrea Bocceli to Adam Sandler, and being butchered by wobbly voiced pop star wannabes on YouTube and talent shows. As more and more artists, both professional and amateur, took their stab at “Hallelujah,” the song would eventually eclipse all of Cohen’s other successes and become his most recognizable composition. So, while the whole world was having a love affair with “Halleljjuah,” what was Cohen’s feelings on its resurgence?

To have a song that the record label originally refused to release become one of the biggest songs of the century obviously gave Cohen a certain satisfaction, but it was reported that he would get understandably irritated when he’d hear it mistakenly credited as a John Cale or Jeff Buckley song. But he obviously understood the importance of the covers that gave it new life, and staring in the late 1990’s Cohen began performing “Hallelujah” with the lyrics that John Cale had chosen for his version. However, after a while, as the song began to get overused, even Cohen himself was getting tired of hearing it everywhere. In an interview given in 2009 Cohen said “I was just reading a review of a movie called ‘Watchmen’ that uses it and the reviewer said – ‘Can we please have a moratorium on ‘Hallelujah; in movies and television shows?’ I kind of feel the same way … I think it’s a good song, but I think too many people sing it.” Well, what can I say? I feel the same way, Leonard.

Now I don’t want to say I hate the song “Hallelujah.” I loved it the first time I heard it, and during recent relistens to “Various Positions,” I began reappreciating it as an important part of Leonard Cohen’s body of work. After multiple deep listens to “Various Positions,” which I hadn’t revisited for a long while, I’ve come to reppreiciate it as one of Cohen’s true masterpieces, but I’m not really sure that “Hallelujah” is the best song on the album (I’d lean more towards “If It’d Be Your Will” to be the standout). But covering “Hallelujah” has become such an unintentional cliché that nothing will bore me more than hearing yet another substandard cover of it. Furthermore, to pin Leonard Cohen’s entire musical legacy on that one song is really an insult to his incredible body of work, especially considering that he had maintained a career with many peaks and valleys for nearly three decades before “Hallelujah” found popularity through the support of other artists. But that’s just my opinion. Much to my chagrin, I am sure there is a singer in a studio somewhere about to record yet another version of “Hallelujah,” continuing the cycle of redundancy that has made it one of the most recognized songs of the century. Although I truly love Leonard Cohen with all my heart, the day people stop recording ill advised covers of that song will be the day I finally exclaim hallelujah myself.